The playwright Jen Silverman is brimming with ideas for her new fact-based drama Spain, which opened Thursday at Second Stage’s Off Broadway Tony Kiser Theater. She touches on the long history of Russian propaganda campaigns overseas, the willful blindness of American progressives, the future of narrative art in the social media era, and even the misogyny that talented women face as they bury their own ambitions to support the work of less-talented male colleagues. She also has gooses her narrative with a couple bold-faced names: the novelists John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway, who in the 1930s were recruited by two Dutch filmmakers to collaborate on the script for a KGB-funded documentary film about the antifascist forces in the Spanish Civil War — a project that aimed to stir American support for ending FDR’s anti-interventionist foreign policy at the time.

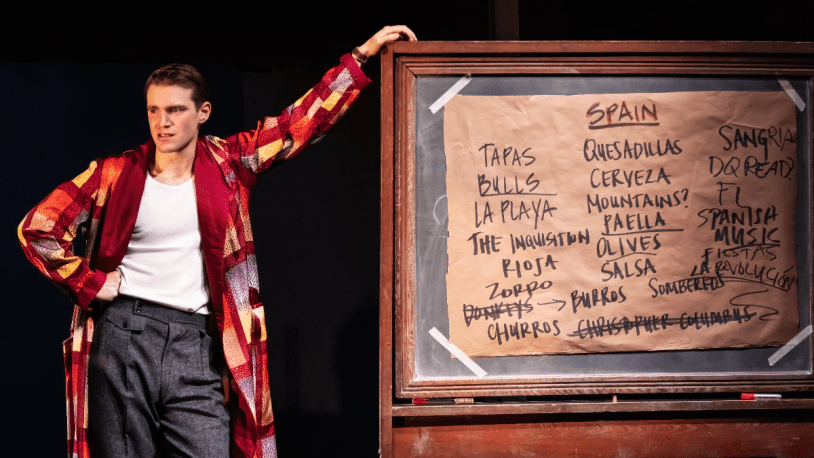

It’s a remarkable story, to be sure. And Dutch documentarian Joris Ivens and his collaborator/editor, Helen van Dongen, really did make a film, 1937’s The Spanish Earth, that screened at the White House and in Hollywood and raised funds for the antifascist cause in Spain. In Silverman’s Spain, Andrew Burnap and Marin Ireland play Joris and Helen as an anachronistically self-aware couple straight out of a ’30s screwball comedy. They bat around high-falutin’ ideas and romantic badinage with charming aplomb, dropping the real names of their Russian handlers even as they admit they should speak more cautiously. In one witty scene, they spitball ideas for their film around the ’30s equivalent of a whiteboard, revealing their ignorance of their assigned country. “Flute music?” “Are flutes Spanish?” “Maybe not.”

When they finally get around to recruiting the novelists to script their film, Dos Passos and Hemingway offer a striking contrast: Dos Passos (Erik Lochtefeld) is the more aloof intellectual, drawn to the antifascist cause out of principles but wary about the unknowable ways that war can change things (“which kind of war doesn’t leave hundreds of thousands of bodies in its wake?”); while Danny Wolohan’s Hemingway is an almost cartoonishly arrogant narcissist drawn to the prospect of covering a war (“the only thing worth making work about for a man”). Silverman has a flair for drawing her characters in quick, broad strokes — making up in theatricality what they sometimes lack in depth or nuance.

As far as the KGB is concerned, Hemingway is clearly the bigger get so Dos Passos is soon sidelined from the film. Zachary James’s opera-loving Russian backer mostly hovers around the action like the henchman in a classic film noir — an effect that is brilliantly underscored in Tyne Rafaeli’s stylish production by Dane Laffrey’s blocky, monochromatic set design and Alejo Vietti’s cinematic lighting. Spain looks incredible, while Burnap and Ireland in particular ground the show with a winsome and disarming onstage chemistry.

The problem is that the show’s charms exist mostly at the surface level, particularly in the storytelling. We never get the sense that this was Hemingway’s first real dip into politics, nor how this project in fact attracted a wider circle of bold-faced names: Orson Welles narrated the film (from Hemingway’s script); Jean Renoir did the French version; Archibald MacLeish and Lillian Hellman outlined the first scenario. The film, and the Spanish Civil War more broadly, became a kind of proving ground for liberal American intellectuals at the time — particularly Dos Passos, who had flirted with communist causes but became disillusioned by the Soviet-backed republic’s brutality and shifted into right-leaning, anti-communist libertarianism.

In effect, Silverman has written the outline for a limited TV/streaming series about this fascinating episode in American and world history — but condensed it into a 90-minute entertainment that is appealingly packaged but frustrating for all its brevity, rapid cuts and necessary elisions. The final scene, which represents a sudden flash forward in time, introduces some provocative new ideas that don’t feel sufficiently foreshadowed to effectively pay off. (The sequence suggests a viable second season for that putative limited series, or perhaps a parallel timeframe.) This is the rare show that you wish had been longer, and more ambitious.