Itamar Moses’s new drama The Ally is willing to go there, to perhaps the most prickly topic for liberal New Yorkers in 2024: the thorny question of Israel and Palestine. In a program note, Moses recounts how he found himself clamming up whenever the subject came up despite engaging in rigorous online debates on any number of other political issues — and chalked it up to his status “as a left-wing, American Jew with Isreali immigrant parents” whose feelings about Israel were “too confused, too contradictory, too raw.”

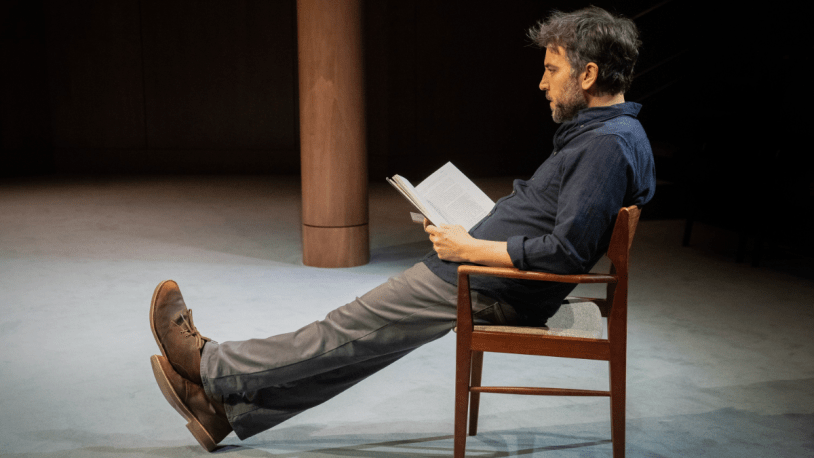

Eventually, he decided to write through his feelings — and the result is this remarkable and timely play that raises arguments and counter-arguments and counter-counter-arguments about different aspects of the issue. Just about every imaginable position is given voice: whether Israel’s treatment of Palestinians amounts to genocide or whether progressives’ quickness to condemn Israel but remain silent about other foreign atrocities is rooted in implicit antisemitism. Moses has centered the drama on an avatar for himself, a successful Jewish American playwright named Asaf played with low-key intellectual befuddlement by Josh Radnor. And he’s dropped his doppelganger in that hotbed of progressive politics and performative allyship: an American college campus, where he’s landed with his administrator wife (Joy Osmanski) as an underemployed plus-one teaching a single writing course every other semester.

There, Asaf is drawn into the Israel debate through circuitous means — a petition for justice after the local police kill an unarmed Black man who happened to be the cousin of one of his former students (Elijah Jones). That petition, which situates the #BlackLivesMatter movement amid a broader push for universal justice, including for Palestinians, soon embroils Asaf in a series of conversations about the Israel question. We meet two young student activists, one Palestinian (Michael Khalid Karadsheh) and one Jewish (Madeline Weinstein, flashing the finger-snapping overeagerness of many a college activist). We also meet a kippah-wearing PhD student in Judaic Studies (Ben Rosenfield), who recontextualizes the pro-Palestinian talking points and suggests how just about any Israeli criticism embolden antisemites. And we meet the petition’s author, a local activist (Cherise Booth) who conveniently happens to be Asaf’s ex-girlfriend.

Moses masterfully presents opposing viewpoints, and director Lila Neugebauer impressively coaxes her talented cast to articulate them without obviously tipping the scale to any one side — and the playwright also studs the polemics with sharp humor. Over time, we watch as Asaf barges into each conversation, shakily repeating elements of the previous speaker’s argument as he muddles his way to a personal worldview he can embrace. Again and again, he struggles to articulate a coherent argument — or to even acknowledge why this subject hits so close to home.

Where the play stumbles, though, is in a rational depiction of Asaf’s key relationships — particularly to a wife who seems here more like a psychotherapist of superheroic forbearance. Radnor’s Asaf remains a puzzling figure — passive and easily swayed one minute, strident and stubbornly clinging to barely coherent beliefs the next — that it’s sometimes a wonder what either his wife or his ex-girlfriend ever saw in him.

Asaf is almost a parody of the out-of-touch intellectual, a latter-day Hamlet so stuck inside his head that he seems incapable of action. Indeed, the plot builds to a key moment of decision, or indecision in his case, over whether he should join a protest march. But bizarrely, this demonstration has nothing at all to do with the Israeli-Palestinian conundrum that has twisted him into knots. As a result, the climax is a bit of a head-scratcher — even the campus rabbi (also played by Boothe) seems flummoxed trying to puncture Asaf’s self-built suit of armor. Still, she smartly reinforces the danger of building a wall between our minds (where we can find safety by turning over ideas forever) and our bodies (which can be hurt, and badly). At some point, she suggests, you need to get out of your armchair and, if not take a stand, at least stretch your legs.