In a program note for his new drama, Corruption, playwright J.T. Rogers explains that his adaptation of the 2012 book Dial M for Murdoch: News International and the Corruption of Britain is a work of “historical fiction” that includes “scenes that are invented whole cloth.” It’s an odd confession for a show whose stated ambition is to expose the modern news media’s shortcomings — and how Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. perverted traditional journalism by illegally hacking into tens of thousands of cellphones of politicians, celebrities, members of the royal family, top police officers, and even regular citizens in a profit-first quest for power and exclusive scoops.

Rogers is no stranger to talky fact-based dramas that rely on a large cast to portray an even larger group of individuals. His 2016 play Oslo, recounting the back-channel diplomacy between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization in the 1990s, went on to win the Tony Award for Best Play. But Corruption, which opened Monday at Lincoln Center Theater’s downstairs Mitzi E. Newhouse venue (where Oslo also premiered) is a talkier and lumpier exercise altogether.

The main problem may be the focus on Dial M for Murdoch co-author Tom Watson (Toby Stephens), a longtime Labour Party MP who served as an attack dog for late 2010s Prime Minister Gordon Brown who then became an outspoken figure on a parliamentary committee investigating the nascent phone-hacking scandal, which everybody from Scotland Yard to the Murdoch empire itself initially downplayed. He’s a sharp-elbowed pol with a tendency to bluster and procrastinate (playing Grand Theft Auto instead of writing a key speech). He’s also dismissive of the legitimate concerns of his wife (Robyn Kerr, who also plays two other roles), and prickly when trying to rally journalists to push the scandal forward. You can see why this self-aggrandizing pol cast himself as the hero of his book, but do we really need a play that valorizes a back-stabbing back-bencher who launched an anti-Murdoch crusade that only kinda-sorta worked?

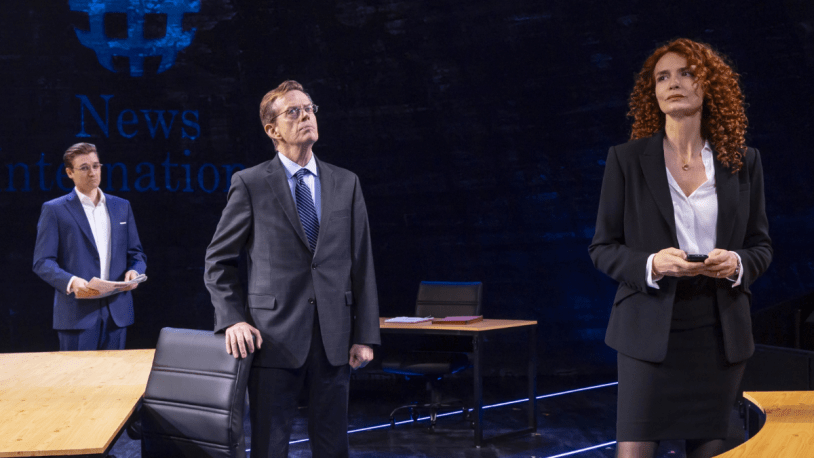

At least the show has a compelling foil in Rebekah Brooks, the imperious editor of the News of the World who defended NewsCorp’s questionable reporting techniques with a fiery tenacity that matched her curly mane of blood-red hair. Saffron Burrows struts about the stage like a high-heeled lioness, able to persuade or needle just about anyone to her side — from politicians to rival journalists to her hen-pecked husband (John Behlmann, who plays four other roles) to a lower-class surrogate (also Kerr) hired to make her a mother — admittedly one with no plans to take any maternal leave time. Every time Burrows’s Rebekah comes on stage, you wish she had been the central role — because hers is the sort of plus-size character that Shakespeare would have relished, a villian with hubris to spare and a canny ability to avoid comeuppance for far longer than anyone would expect. (Even in disgrace, ousted from her job and placed on trial for her wrongdoing, she finds a way to endure: In 2015, she was reinstated as CEO of Murdoch’s UK news operation.)

Rogers revels in the minutiae of the phone-hacking scandal, and there are some intriguing details strewn along the path, along with some telling takeaways about how even crusaders can be willing to compromise their values in the quest for a Greater Truth.

Director Bartlett Sher keeps the action moving — literally. No scene lasts more than a few minutes, which means the cast is constantly jumping into new roles and shuffling office furniture about the circular stage to create different locales (parliamentary chambers, boardrooms, newsrooms, bars, and living rooms primarily). But Roger’s main approach is to tell, not show, and he seems to have volumes to tell us. About U.K. politics, about the media industry’s shift toward profit at all costs, about the Murdochs (though we never see Rupert himself). This is a timely story with a whole lot to say, but the cumulative effect is mostly exhausting.