Peter Morgan is no stranger to historical dramas based on the recent past, with real-life characters who are often still alive. His credits include Frost/Nixon, The Queen, and the TV hit The Crown, which share both a verisimilitude as well as a willingness to gently bend the factual record to serve up thematic truths. His latest drama, Patriots, is an insanely timely look at the rise of Vladimir Putin as the leader of Russia — and it has all the epic sweep and emotional heft of any Shakespearean tragedy.

As the audience knows all too well, the tragic figure at the center is not Putin himself (played by Will Keen in a riveting performance) but a Russian Jewish oligarch Boris Berezovsky (Michael Stuhlbarg), who plucks Putin from bureaucratic obscurity and engineers his rise from deputy mayor of St. Petersburg to director of the Federal Security Service to prime minister and eventually finagles his appointment as the successor to President Boris Yeltsin (Paul Kynman). But Putin, whom he dismisses as a short, grey man who inexplicably refuses his offers of luxury cars and kickbacks, also does not feel beholden to Berezovsky once he has won election to Russia’s highest office.

Stuhlbarg and Keen offer a remarkable contrast in the physical presentation of unbridled power despite the fact that both are both balding men of relatively short stature. As Yeltsin’s daughter and adviser Tatiana (Camila Canó-Flaviá) comments prophetically, “He feels little. Little is dangerous. Little, in my experience, only ever wants to be perceived as big.” While Stuhlbarg’s Berezovsky is an excitable man, pulsing with impatient energy and willing to physically bully people who dwarf him in size, Keen’s Putin is an avatar of coiled anger waiting to pounce. Keen often stands with his right arm rigidly at his side, as if ready to draw a firearm at a moment’s notice, and his right hand frequently quivers in Parkinson’s-like spasms from having to hold that position for so long. When he does explode, it is with the barely contained restraint of a general who need not fire a shot himself, making his outburst all the more deadly.

Morgan sketches a fascinating portrait of Berezovsky, a math prodigy from a humble family in the Russian provinces who eventually abandons his studies of pure mathematics for the more lucrative world of finance — particularly as the Soviet Union’s collapse enables crafty individuals like him to amass almost-total control over state-owned industries. Berezovsky is flying high, accumulating car companies and the state TV network as well as a St. Mortiz-shopping mistress (Marianna Gailus). He even mentors younger entrepreneurs like Roman Abromovich (Luke Thallon), with whom he partners on the oil giant Sibneft and who urge him to tow the line with Putin.

But Berzovsky’s quest for power also leads him to place his bets on Putin, whom he sees as a puppet he can control as he expands his personal fortune. Learning that Putin spent his early days in the KGB office in Dresden, Berezovsky is all too quick to dismiss Putin, and, even more riskily, to his face. “East Germany is where they sent the desk- jockeys, the altar boys, the softies, the ‘B’ team. Isn’t that right? The alphas, the psychos, the real KGB men of action got sent to London and Washington to do the proper work.”

As if to disprove that characterization, the Putin that emerges once he claims the presidency is very much in the “real KGB men of action” mold. He’s quick to denounce oligarchs as “self-interested crooks” who “are not just rich, but obscenely rich.” He sees his election as an actual mandate from the people to serve their interests, and to not feel beholden to patrons who had facilitated his ascent. And he senses Russia’s innate suspicion of real democracy, and soon adopts the posture of a Soviet-style strongman who cannot tolerate real dissent. Berezovsky, who early on articulates an interest in the mathematics of decision-making theory, makes a fundamental miscalculation about Putin and his own ability to steer Russia’s future and soon emerges as a lone oligarch on the sidelines of power.

Morgan’s script has a Shakespearean sweep, presenting Berezovsky and Putin as dueling dark heroes seeking to shape Russia’s future. Berezovsky’s fatal flaw is his inability to yield, to kiss Putin’s ring and accept any modifications in his vision. Before long, he finds himself in exile without his TV network or much of his empire — while the more accommodating Abromovich becomes even richer and more powerful. (Abromovich is now said to be worth $14.5 billion — though many of his assets were frozen following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.) Even holed up in a London mansion, Berezovsky and his inner circle are unable to escape the long, deadly reach of Putin’s wrath. Neither is the forgive-and-forget type.

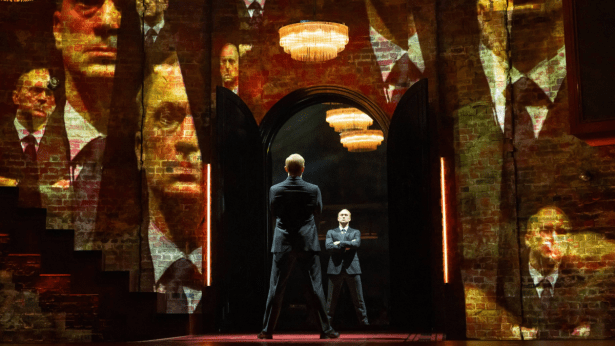

Director Rupert Goold captures the epic scope of the text with a production that makes smart use of Miriam Buether’s sleek brick turret set (with an overhead anchorman desk), bold video projections (designed by Ash J. Woodward), and smart costumes (by Buether and Deborah Andrews) that illustrate Putin’s rise in power, from ill-fitting suits to crispy tailored power statements. He also commands a large cast of 16 (many playing two or three roles) with a precision and clarity that carry through the script’s bumpier patches, like a second act that can meander through Berezovsky’s all-too-obvious comeuppance.

While the action ends before Putin’s invasion of Ukraine — Berezovsky died in 2013 in an apparent suicide that some have questioned as suspicious — the shadow of that endeavor loom heavily over Patriots. We see how even an unlikely figure can seize a moment, and almost unchecked power, and bend a state and its tools to his will. Patriots is political drama at its most urgent, as relevant as today’s headlines, with a psychological complexity and a dark humor that make it crackling entertainment.