There are some individuals who, either by their nature or the nature of their psychiatric condition, seem to be utterly resistant to therapy. The young woman in Max Wolf Friedlich’s explosive new two-hander Job takes that resistance several steps further. (The show opened Wednesday at Broadway’s Hayes Theater after runs at several Off Broadway venues.) She opens the first session by pointing a gun at the therapist, a sixtysomething man with a hippie-adjacent look played with preternatural calm by Peter Friedman. In a series of rapid-fire scenes lasting only seconds each, we see various scenarios play out, from her remaining frozen to firing at him to turning the weapon on herself. And then, as if the spell has been broken or the adrenaline rush has subsided, we settle into the most awkward therapy session in history.

The woman, a twentysomething full of entitlement and rage and not fully aware of either her illness or her internal contradictions, has clearly been scarred by her years working as a content moderator for a tech giant that’s never named. (She’s also been shaken by earlier traumas, which she shares with a characteristically bitter wit but no self-awareness.) After years of watching violent, disgusting images, she suddenly snapped — producing a viral video of standing-on-a-desk rage that has landed her in this therapist’s office. She is seeking his approval to reclaim her job, which she treats as a vocation with an almost missionary zeal: “For the first time in my life I have power. Or had.”

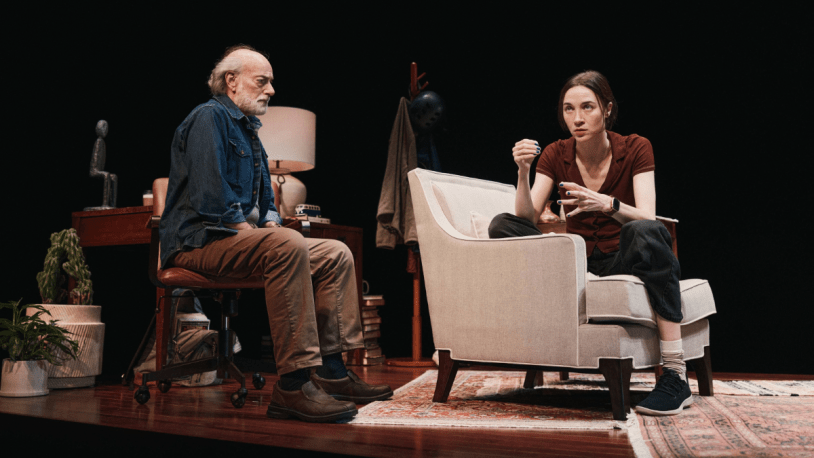

Sydney Lemmon is phenomenal as the young woman, identified as Jane in the script, projecting intelligence, sarcasm and solipsism in equal measure — and she sometimes manages to make us forget about the depths of her paranoia (she insists on looking at, and approving, the text that Friedman’s therapist sends to cancel his next patient). Mental illness does not usually come in this articulate and put-together a package.

Friedman, meanwhile, matches Lemmon’s performance with a savvy intelligence all his own, engaging this troubled patient while making us ever aware that this is a hostage situation in which the doctor does not hold the upper hand, even after Jane’s gun is momentarily tucked away in her cloth bag. No therapists are trained to handle a session quite like this one, but Friedman projects an outward calm even as he scrambles for ways to defuse a situation that could end his life as well as his career. “We are both people saddled with a calling,” he tells her at one point. “Mine is to care for the young woman here in this room. Not some cog in a corporate machine, not some viral video, but a person who has earned the right to be taken seriously.”

Director Michael Herwitz strikes the right balance in the back-and-forth between the two characters, moving them about the cramped, simply designed set (by Scott Penner) in ways that seem natural. And sound designers Jessie Char and Maxwell Neely-Cohen, working with lighting designer Mextly Couzin, add elements that amplify our sense of Jane’s disorientation, the episodes where she seems to be drifting out of the reality of the moment.

Over time, Friedman’s character begins to suggest an alternative take on the show’s title: Like the biblical Job, this therapist is subjected to one trial after another, each testing his faith (in therapy) as well as his ability to survive. Yes, he occasionally flashes arrogance and can be quick to dismiss a younger generation’s dependency on technology. But somehow, he faces each obstacle patiently and forthrightly. That includes a final accusation/revelation by Jane about his supposed past that feels far too rushed for either the characters or the audience to fully process, or weigh the truth of. This buzzy twist, which generated much discussion during the show’s Off Broadway run, still strains credulity despite some tweaks to the script and the physical production.

In the end, I don’t think Friedlich (and Herwitz) go far enough to even the scales between the two sides — or to introduce the central conflict early enough to draw a fair conclusion based on circumstantial evidence. On the surface, it’s a dramatic role reversal that should have us reassessing everything that’s come before. But I don’t buy it — despite the cast’s considerable efforts. Lemmon’s Jane is such a smooth talker, so resistant to accept alternative points of view, that it can be easy to forget how unreliable a narrator she is when it comes to her own life, let alone the lives of others. Despite my quibbles, Job is a crackerjack battle of the generations, a smart and nuanced study of two people whose lives are forever changed when they cross paths.