Igor Golyak, who directed the remarkable Holocaust drama Our Class that played this year at both BAM and the Classic Stage Company, seems drawn to stories about humanity’s dangerous impulses toward antisemitism. So it should come as no surprise that his latest work is an imaginative Classic Stage revival of William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, that most problematic of the Bard’s problem plays, whose depiction of the money-lending Jew Shylock has vexed theater companies for centuries.

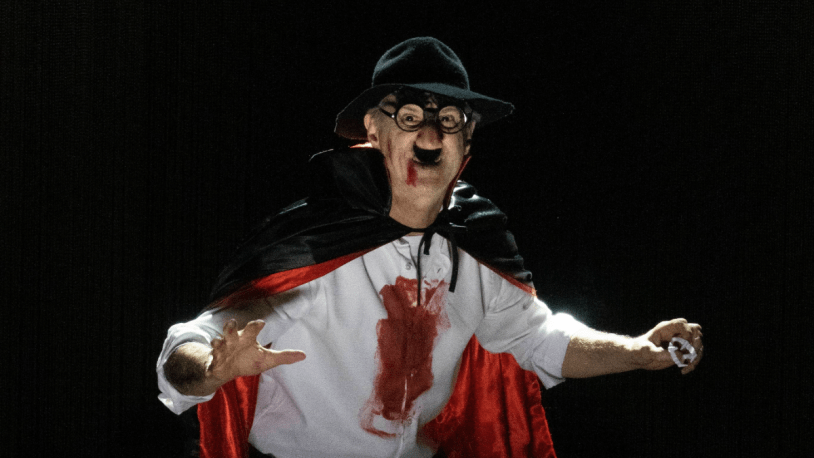

Richard Topol, who in Our Class played the America-bound classmate of Polish schoolchildren torn apart by the Holocaust, here dons plastic Groucho Marx glasses and nose, as well as a blood-smeared shirt and occasional vampire teeth, to play a hyperbolic version of the supposedly villainous Shylock — who is dismissed and mocked by just about every character, including his daughter, Jessica (Gus Birney), who elopes with a Christian (Noah Pacht) and steals much of her father’s fortune as she goes.

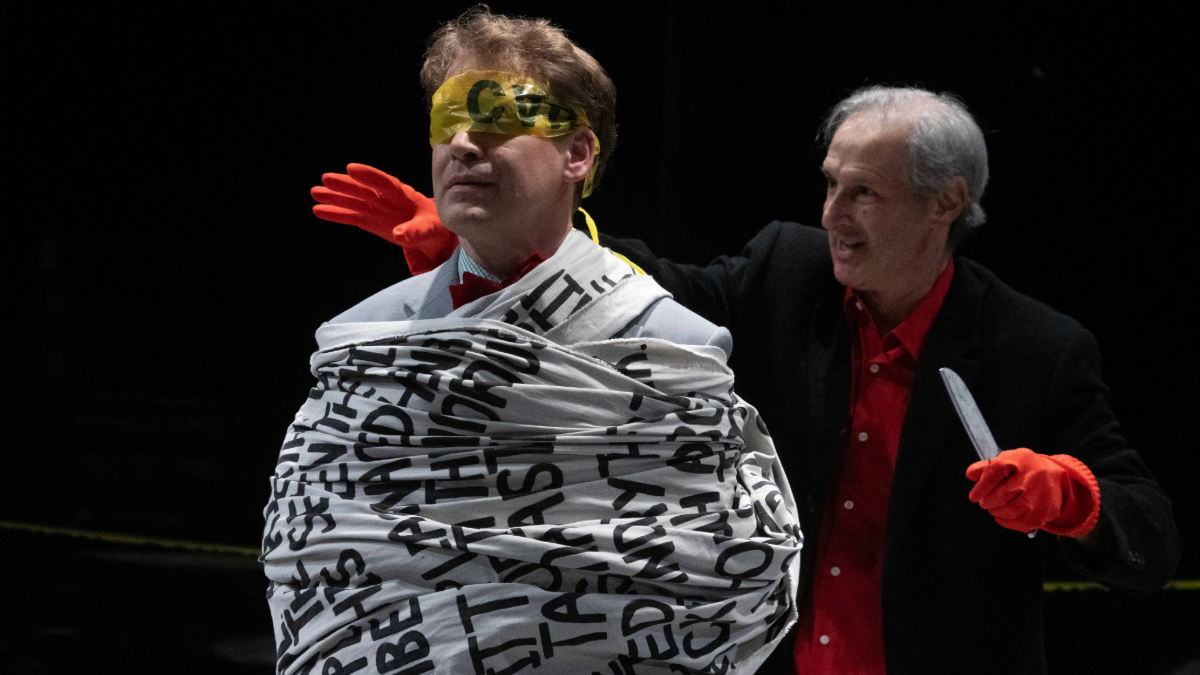

Golyak leans into the play’s origins as a comedy, in name at least. He bring out a grab-bag of tricks: exaggerated performances, slapstick humor, anachronistic ad-libs, a unicycle, outrageous modern-day costumes (Sasha Ageeva), and even a one-man band (Fedor Zhuravlev) who supplies rimshots to punctuate the punchlines. He also introduces a meta element, imaginging the whole production as a no-frills cable-access show hosted by the Venetian merchant Antonio (T.R. Knight), who becomes the target of Shylock’s vengeance when his ships are lost at sea and he can’t pay back the 3,000-ducat loan he took from Shylock. There are even “applause” and “boo” signs to signal how the in-house live audience should respond. Plus, the talented Stephen Ochsner channels Harpo Marx in several delightfully over-the-top physical comedy bits, playing an overalls-clad assistant stage manager who scurries about setting up the camera and props while also “filling in” as multiple characters after a chunk of the cast, we learn early on, walked out after a disastrous dress rehearsal.

As in Our Class, Golyak has a flair for stagecraft on a shoestring — here deploying everything from puppets to dance breaks to bubble guns to vocal impressions to video projections (as it happens, the show could have benefited from more live video). José Espinosa, buff and believable as the overspending trust-funder Bassanio who’s the beneficiary of Antonio’s loan, gets big laughs playing the rival suitors for the hand of the orphaned heiress Portia (Alexandra Silber, nailing her pretty-in-pink Paris Hilton persona). Competing in a kind of international version of The Bachelorette, he rattles off a series of random words in Italian, French, and soccer-hooligan British accents that render Bassanio Mr. Not Wrong by default.

There’s a sense of play here that’s often charming but can just as frequently miss the mark, especially since Golyak’s adaptation mostly involves doubling and tripling up roles (the cast numbers just eight, not counting the musician) rather than making substantial trims to the Bard’s original text. (Shakespeare’s poetry takes a back seat to the straining for another joke.) The production runs over two hours, without an intermission, and it frequently drags — there are long scenes that don’t serve the plot and aren’t very funny, like one of those post-midnight SNL sketches that you beg will go to commercial far sooner than it does.

The bigger problem is that Golyak hasn’t worked out how to handle Shylock even as the show veers into more dramatic territory in the final third. Topol begins to shed his Groucho glasses and exaggerated performance style, even answering the question of a courtroom lawyer (Portia in disguise) about his identity: “Shylock… Richard is my name.” (Shakespeare is silent on the character’s actual first name.) But the show doesn’t sufficiently establish Shylock’s transformation from a panto-perfect cartoon villain into a wronged Jewish man with an understandable desire to lash out at his antisemitic oppressors. That’s particularly true in the climactic moment in which Shylock demands his “pound of flesh” from the debt-ridden Antonio, who knowingly accepted the terms of the deal and the stiff penalty for defaulting. (It’s a nice touch for Shylock to bring out a talking bathroom scale to weigh Antonio first.) When Topol’s Shylock hovers behind a bound-and-gagged Antonio, after tossing aside the obviously rubber stage cleaver for a more realistic knife, there’s never any real sense of danger because the moment seems to come out of nowhere.

I think I see Golyak’s intention here, and he’s actually built a show-within-a-show framework where this sudden and dramatic shift in tone might work. But that would require more meta scenes from The Antonio Show where Knight as master of ceremonies and the rest of the cast are badly treating Topol (as opposed to his onstage character). Such an approach might have deepened the impact of the ending, including the ultimate reversal of fortune for Shylock (who not only surrenders the contract he’s fought so hard to enforce but also agrees to convert to Christianity). It’s a comeuppance that has complicated the play’s legacy, to say the least. While it’s Shylock who takes a pounding in the end, this Merchant of Venice never quite reconciles its comedic or tragic threads in its quest to offer pounds and pounds of flash.

THE MERCHANT OF VENICE

Classic Stage Company, Off Broadway

Running time: 2 hours (no intermission)

Tickets on sale through Dec. 22