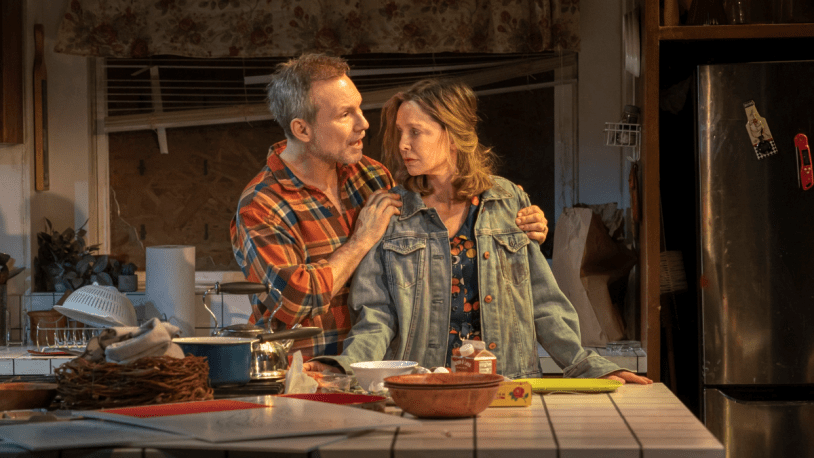

It was only six years ago that Maggie Siff led a solid but workmanlike revival of Sam Shepard’s 1978 drama Curse of the Starving Class. Now Calista Flockhart and Christian Slater are returning to the New York stage after a decades-long absence in a New Group production that seems dialed-down to the point of somnolence. Flockhart and Slater play the heads of a dysfunctional rural California family that seeks escape by any means within their grasp: Flockhart’s Ella, fed up with her absentee alcoholic husband and perpetually empty fridge, wants to woo a smooth lawyer (Kyle Beltran) into selling their land and moving off to Europe. Meanwhile, Slater’s Weston considers his own scheme to sell the land and pay off his mounting personal debts, at least in those occasional moments when he’s not passed out drunk or in the midst of an alcohol-fueled rage.

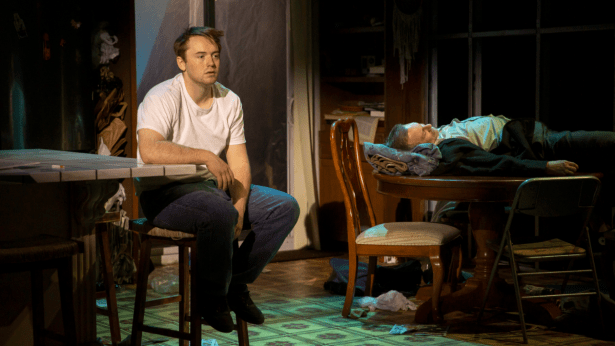

Their solipsism leaves little room for their kids, the sullen teenager Wesley (Cooper Hoffman) and 13-year-old high achiever Emma (Stella Marcus), who both yearn to break the generational pattern of self-defeating behavior but seem ill-equipped to do so. Wesley seems the most keenly aware of their dilemma, suppressing his desire to find a new frontier like Alaska and instead make the best of it on the much-depleted homestead. “It’d be the same as it is here,” he scoffs at his mother’s suggestion that they move to Europe. When Ella insists they’d be in “a whole new place, a whole new world,” he quickly responds, “But we’d all be the same people.”

Alas, there’s an even-keeled sameyness to the cast’s portrayals that undercuts the reversals that Shepard unleashes in the final act. Flockhart’s Ella seems like neither a schemer nor a seductress early on, while Slater brings a wry, laid-back energy to most of his scenes that fails to deliver much of the hair-trigger menace that we keep hearing about from the rest of the family. They deliver the lines, frequently at high volume, but none of them feel lived-in. Hoffman, the son of the late Shepard veteran Philip Seymour Hoffman, seems mostly ill at ease and underprepared, and not just in the flashy scenes that require him to strip naked or urinate on his sister’s 4H project. During the spotlit monologues by his castmates, he consistently pulls focus from whoever’s speaking by looking around and fidgeting with a restless, ever-bouncing left knee. Only Marcus seems to convey a consistent feistiness, though her transition to rebel outlaw late in the show feels a bit too abrupt.

Director Scott Elliott doesn’t help matters with some curious choices, beginning with a visual look that suggests a more contemporary setting than Shepard imagined. Catherine Zuber’s costumes include hoodies, while Arnulfo Maldonado’s set features a microwave and low-end stainless steel fridge that are wildly anachronistic for a family headed by a man who drives a Packard and recalls flying B-49 bombers over Italy in World War II. Maldonado’s set also features a shattered sliding glass door — the result of one of Weston’s violent drunken spells — when the characters repeatedly talk about him busting through a wooden door. (Was Maldonado not given a script before they settled on a design?) All too often, the disconnect between what we’re hearing and seeing is too jarring and distancing, ironically underscoring just how dated Shepard’s half-century-old approach to class issues now appears. (The play, a bridge between the between the absurdism of Shepard’s early plays and the hyper-realism of later works like the Pulitzer winner “Buried Child,” employs many on-the-nose metaphors and heavy-handed speechifying to drive home its message.)

Elliott also undercuts the careful three-act structure of Shepard’s play by placing the intermission in the middle of the second act. In one sense, the decision makes sense. The show already runs 2 hours and 45 minutes, and a second intermission might push the production closer to the off-putting three-hour mark. But Shepard’s composition is deliberate, both on a practical level to make major changes to the scenery and set-up of the kitchen/dining area (now performed in dim lighting by the actors themselves) but also to mark the passage of time and the shifts in the characters’ mindsets. Those transitions now come way too abruptly to register coherently, a problem that’s exacerbated by performances that are notably flattened for a family that we’re told is so volatile it has nitroglycerine running in its blood.

The strongest performance comes from a four-legged scene-stealing sheep (here played by a woolly looker named Lois) who seems genuinely fascinated when Slater’s Weston delivers a meandering yarn about a determined eagle that dive-bombs onto a shed roof in a determined display of a predator’s power. Weston is interrupted in his story — and we only hear the parable’s tragic end in the show’s final moments — but there’s a sense of connection and engagement that the rest of Elliott’s production sadly lacks. ★☆☆☆☆

CURSE OF THE STARVING CLASS

The New Group at Pershing Square Signature Center, Off Broadway

Running time: 2 hours, 45 minutes (1 intermission)

Tickets on sale through April 6 (tickets: $43-$119)