Nearly two decades have passed since George Clooney directed and co-wrote Good Night, and Good Luck, a black-and-white drama depicting beloved CBS newsman Edward R. Murrow’s challenge to Sen. Joseph McCarthy during the Red Scare fervor of the 1950s that sought to root out communists from U.S. society. The film earned six Oscar nominations, including for Clooney’s direction and script (with Grant Heslov), and won mostly raves for its timely critique of conservative extremism and the corporatization of big media.

Those issues remain just as urgent today, of course, which may explain why Clooney and Heslov have adapted their screenplay for a notably cinematic stage version, in which the star makes his Broadway acting debut as the saintly Murrow (a role that David Strathairn played on film). But this production, directed with swift efficiency by David Cromer, is a curious exercise in re-creating the experience of a film in a new medium. We get quick, rapid-fire scenes that blend into each other; handsome set pieces (by Scott Pask) that move on and off the stage of the Winter Garden Theatre to represent various offices, soundstages, and other locales; and a multitude of LED screens that float in and out of view, or line the sides of the stage, or loom in the background — often depicting actual archival footage of McCarthy and interview subjects from Murrow’s See It Now news show, as well as some hilarious period commercials (David Benjali designed the projections).

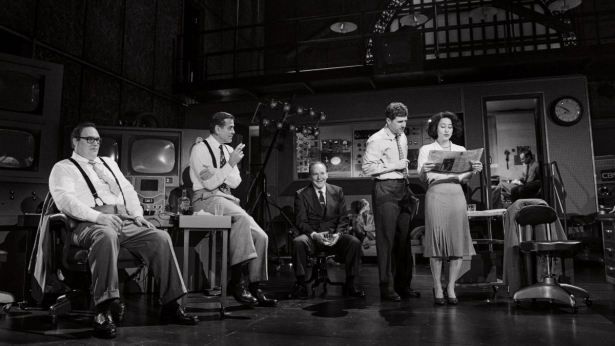

It seems that no expense has been spared here — including filling that vast TV-studio set with a cast of 22, many of whom get only a handful of lines (if any). Bizarrely, there’s also a live four-piece band, hovering over stage left in a recording studio space with an actress (Imani Rouselle filled in for Georgia Heers at my performance) crooning period tunes between scenes in the manner of Ella Fitzgerald.

The show introduces a lot of characters, mostly white males in suit and tie (sometimes without jackets), and it can be hard to distinguish among them since we don’t have the benefit of closeups. Nor do Clooney and Heslov really flesh out any of the subplots, including a compelling one about two married news writers (Ilana Glazer and Carter Hudson) who must keep their open-secret relationship under wraps due to network rules against fraternization. The script also assumes the audience is generally familiar with the drama’s key figures, McCarthy and Murrow especially, with little in the way of exposition or background for younger theatergoers. Because the show doesn’t linger for very long on any of the characters, Murrow included, none of them really stand out in a way that compels our sympathy — including one who meets a tragic fate toward the end.

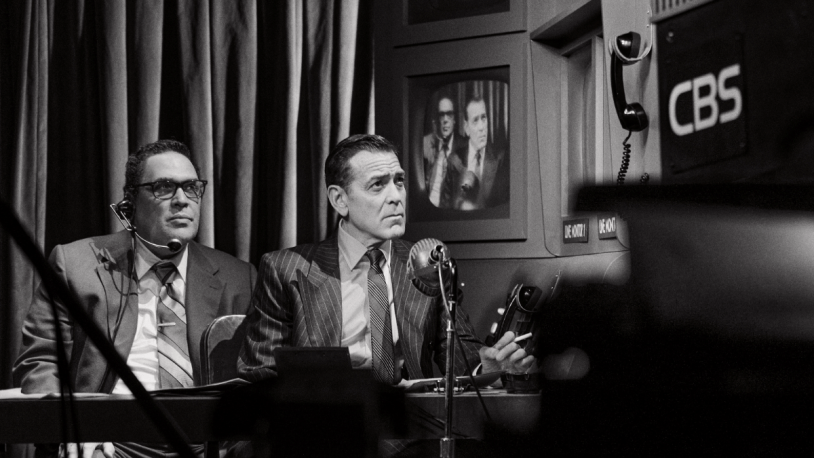

Clooney certainly has the gravitas to play Murrow, whom he plays with an admirable restraint. This is a crusading journalist who visibly drops his face the moment he’s finished a lightweight (and real) interview with a 35-year-old Liberace, signalling that his real interest rests in more serious reportage like the kind challenging McCarthy’s ill-founded attacks on Americans for even the loosest associations with left-wing causes. He nicely balances between the fervor of some of his younger staffers and the skittishness of network president William Paley (a too-genial Paul Gross) — who fears the loss of advertisers if Murrow pursues the McCarthy story too strongly, correctly as it turns out. Clooney’s Murrow is an all-around stand-up guy, and the show allows no chinks in its hero’s armor — or acknowledgement that other media figures also played a role in toppling McCarthy’s authority.

Clooney ably delivers the show’s central message in a speech that bookends the show. “We are currently fat, comfortable, and complacent,” he proclaims from a podium, an address Murrow actually delivered at an industry event five years after his ground-breaking McCarthy broadcast. “Unless we get up off of our fat assets and recognize that media, in the main, is being used to distract, delude, amuse, and insulate us, then those who finance it, those who profit from it, those who work at it and those who consume it may see a totally different picture too late.” It’s a call to arms for both media workers and consumers that still holds in its prescient urgency — and it’s goosed by a video montage that takes us from Murrow’s era right up to the present Elon Musk-shadowed moment. That message still comes through loud and clear in Clooney’s 2005 film. All too often, the stage version feels like a noble but unnecessary repeat. ★★☆☆☆

GOOD NIGHT, AND GOOD LUCK

Winter Garden Theatre, Broadway

Running time: 100 minutes (no intermission)

Tickets on sale through June 8 for $176 to $799