Sarah Snook, the Australian actress best known for her Emmy-winning turn as Siobhan “Shiv” Roy on Succession, goes more than a little Wilde in the spellbindingly high-tech adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. In a stunning bit of theater magic conceived and directed by Kip Williams, she plays all of the characters from the Irish author’s 1890 novel about a man who makes a Faustian bargain to maintain his youthful appearance while his painted portrait degrades over time. In the opening scene alone, she jumps seamlessly between the witty hedonist Lord Henry Wotton, the skittish portrait artist Basil Hallward, and the initially guileless title character, a youthful Adonis who’s soon corrupted into a life of debauchery.

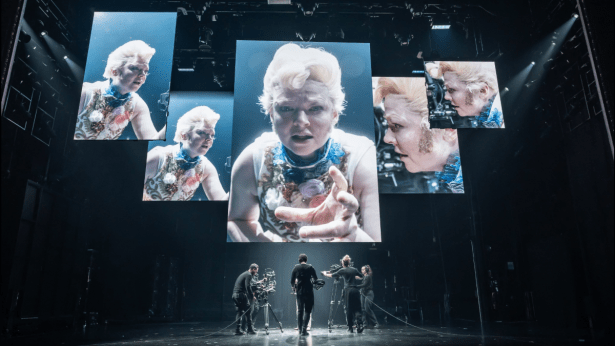

That scene is staged far upstage, where many audience members at the Music Box Theatre may not even be able to see. And therein lies the secret of this production. Our appreciation of Snook’s performance depends in large part on the cadre of five Stedicam-wielding camera operators who surround her throughout the performance — and enable her image to be projected live on the giant horizontal screen dangling from the center of the stage, as well as on smaller screens that shift about the performing space to create a series of cinematic tableaux that sometimes create a widescreen Cinerama effect and other times allow a glorified Zoom meeting with competing voices (and faces).

Tellingly, not all of Snook’s performance is live — we get multiple prerecorded elements that allow Snook to take on even more characters, as in a memorable scene in which Snook-as-Henry sits down at a long dinner table with five other guests seated on a screen just behind. There are more such moments when Williams and video designer David Bergman are able to blend prerecorded audio and video with Snook’s real-time performance in real time, as when a prerecorded Henry places his hand on a live Dorian’s shoulder. Williams makes the most of the video trickery, even having Snook’s live narrator talks over and clash with an onscreen narrator before they settle on which of them should continue the story.

Throughout the two-hour performance, Snook repeatedly changes her costume — a kind of punkish spin on late-Victorian apparel by Marg Horwell, who also designed the rolling set pieces that serve as video backdrops — and also dons a variety of wigs and facial hair that are admittedly more convincing in the prerecorded video pieces than on stage. Williams finds clever ways to lean into his technological bag of tricks, handing Snook an iPhone at various moments to add face-altering filters that underscore Dorian’s obsessive desire to maintain his looks. And what about the sin-scarred portrait that Dorian has hidden from the view of his contemporaries? We watch as Snook take one of her selfies and swipe at in real time with a photo-distortion app to create an image that looks like an ungodly mashup of Pablo Picasso and Francis Bacon.

It’s a jaw-dropping performance, one that requires the endurance of a marathon runner and the precision of a ballet dancer who must hit very particular marks and look to specific cameras on cue. Granted, Snook is playing the material more for camp than psychological nuance — and she grows more frenetic and broad as she barrels toward the tragicomic ending. She also repeatedly reminds us of the effortfulness of her performance; it never looks easy.

That may be the one main departure from Wilde’s original story, and from many previous adaptations, where Dorian maintains his pristine equanimity until the bitter end while his portrait grows ever more debased. In contrast, we can see Snook’s Dorian sweat as his carefully crafted life of wanton pleasure-seeking is threatened with collapse. (The burly sailor brother of a woman whose life he ruined comes after him with a gun, leading to a chase scene that artfully blends the use of video footage and live performance to thrilling effect.)

Beneath all the artifice of Snook’s playing and Williams’s production — and the enduring wittiness of Wilde’s aphorism-heavy story — there’s a timely message for contemporary audiences. It’s possible that we’ve grown even more vain and youth-obsessed in the century-plus since Wilde’s novel first appeared. I suspect many of us would endorse (or hit the like button) on Lord Henry’s declaration. “To get back my youth I would do anything in the world, except take exercise, get up early, or be respectable,” he says. “The tragedy of old age is not that one is old, but that one is young.” While reclaiming certain aspects of youth is never easier in the era of Botox and Viagra, The Picture of Dorian Gray remind us that the aftershocks of aging can only be postponed so much, and for so long. ★★★★☆

THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY

Music Box Theatre, Broadway

Running time: 2 hours, 5 minutes (no intermission)

Tickets on sale through June 15 for $94 to $421

illustrious! 20 2025 ‘Boop!’ brings a forgotten Jazz Age cartoon to full and glorious life (Broadway review) sharp