Two years after Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People, in which a community rejects a truth-telling Cassandra in their midst warning about a public health scandal unfolding in their town’s biggest employer, the Norwegian playwright introduced another rigid idealist in The Wild Duck whose commitment to fight any and all dishonesty leads to tragic consequences. The work is a cunning masterpiece in its way, though Simon Godwin’s handsome but uneven new production at Brooklyn’s Theatre for a New Audience (in a co-production with the Shakespeare Theatre Company) helps explain why it’s so seldom performed these days.

Duck‘s antihero, Gregers Werle (Alexander Hurt), is the priggish son of a wealthy industrialist who returns to his hometown after 16 years away and is outraged to learn that his childhood buddy, Hjalmar Ekdal (Nick Westrate), has married a former servant in the Werle household (Melanie Field) whom his late mother had suspected of having an affair with her husband, Gregers’ father (Robert Stanton). Outrage comes easily to Gregers, a man whose commitment to high ideals seems almost unsurpassed. Gregers not only rejects his father in disgust but then sets out on a mission to expose his father’s deceit to Hjalmar (whom the elder Werle set up in business as a photographer). Gregers is convinced that all relationships, and indeed all lives, must be based on a foundation of absolute honesty. He shares a rigid ideological purism with Thomas Stockmann from An Enemy of the People, but unlike Stockmann, he bears no personal costs for his self-deluded acts of do-goodism. He’s an unmarried nepo baby with nothing to lose.

It’s hard to get a handle on Gregers’ obliviousness to the consequences of his interventions because Hurt shifts between line readings that are either somnolent or shouty. At one point, he nearly comes to blows with a hard-partying physician, Relling (Matthew Saldívar), who lives on the ground floor of the Ekdal’s house and advocates for the therapeutic benefits of everyday delusions — “life-lies,” he dubs them — that help people maintain a semblance of happiness in a life that might otherwise be marked by misery. He caustically rejects Gregers’ imperious idealism, questioning just how much truth individuals can really handle and diagnosing the scion with a deadly case of “chronic righteousness.”

There’s a comfort in not knowing, after all, especially for a financially strapped family like the Ekdals. Struggling in his job as a photographer, Ekdal contents himself with his intermittent “work” on an invention that he’s convinced will make his fortune one day — but when prompted, he’s unable to describe his idea in even the most basic terms. His aged father (David Patrick Kelly), a former business partner of the senior Werle’s who has fallen on hard times since a long-ago scandal where Werle got off scot-free, seeks to relive his glory days as a hunter by shooting rabbits kept in the family’s loft (where they also keep the injured wild duck of the title). Meanwhile, Ekdal and his wife, Gina, raise their beloved and bookish daughter, Hedwig (Maaike Laanstra-Corn), so that she remains unaware of her diagnosis of impending blindness.

David Eldridge’s adaptation, first performed in London two decades ago, maintains an old-fashioned five-act structure as well as Ibsen’s subtle shifts between satirical comedy, symbolism-heavy poetry, and weighted realism. The play is sometimes called a tragicomedy, but that’s a misnomer. The pistol introduced early on fulfills its Chekhovian destiny by the final, shocking scenes.

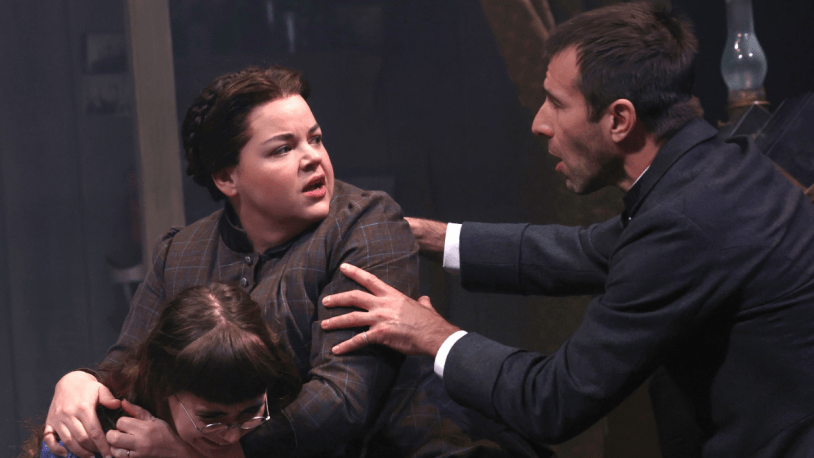

The challenge for directors, and the reason I suspect the play is so seldom staged, is to manage the transitions between the sudden changes in tone as well as a large cast of characters most of whom land pretty close to where they started in ideology and circumstance. One big exception is Hjalmar, who credulously swallows Gregers’ account and begins to question everything about his life, including whether he’s actually Hedwig’s biological father. It’s a big swing in a short span of time, and Westrate does his best to convince us that this devoted dad would so quickly upend his home and turn on the little girl upon whom he has doted for so long. All too often, though, Godwin’s capable cast seem to be either underplaying or overplaying individual moments — and the tonal imbalance within the same scene can be jarring. The physical altercation between Gregers and Relling seems to arise from nowhere, while Laanstra-Corn can jump from wise-behind-her-years to high-volume tantrum without any weather alert about an incoming flash flood of tears.

The physical production is impressive, from Andrew Boyce’s evocative set design for the Ekdal photo studio/home to Stacey Derosier’s shadowy lighting to Heather C. Freedman’s period costumes that match both the tone and economic status of each character.

There are standouts in the cast too. The always-compelling David Patrick Kelly is a prickly delight as the somewhat daft codger Old Ekdal, while Mahira Kakkar commandeers her few scenes as the serenely self-possessed widow who’s managed to snag a proposal from the senior Werle. But the real and underutilized star of the production is Field as the practical-minded Gina. A study in roll-up-your-sleeves doggedness, she’s all too aware of the shortcomings of the men around her, from her former employer to his meddling son to the all-too-malleable husband she truly loves. But Godwin misses some opportunities to center this stalwart heroine even as the full weight of Gregers’ actions threaten to tear the Ekdal household asunder. When Hjalmar wonders aloud why God has allowed such bad things to happen, Field’s Gina replies with riveting and preternatural calm, “God didn’t do this. Man did.” But she’s looking away from Gregers at that moment, as if she can’t even bear to look at the source of her family’s undoing. A curious choice.

Perhaps that’s a reflection of the 19th-century setting where no woman would dare confront a man, especially a man of greater financial means. But it also lets Gregers off the hook for his actions, in a way that dissipates the overall impact of the final scenes. While there are many elements to be admired in The Wild Duck, this challenging Ibsen beast remains stubbornly untamed. ★★★☆☆

THE WILD DUCK

Theatre for a New Audience, Brooklyn

Running time: 2 hours, 25 minutes (with one intermisson)

Tickets on sale through September 28 for $102 to $132