Tim Blake Nelson, the beloved character actor best known for his work in Coen Brothers films like O Brother, Where Art Thou? and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, continues his foray into playwriting with a timely and thoughtful new dystopian drama, And Then We Were No More. The play, which opened Sunday at LaMaMa in an evocatively staged production directed by Mark Wing-Davey, imagines a near-future where criminal justice is dispensed mostly by algorithm from a fortress of a building that dominates the skyline of an unnamed metropolis.

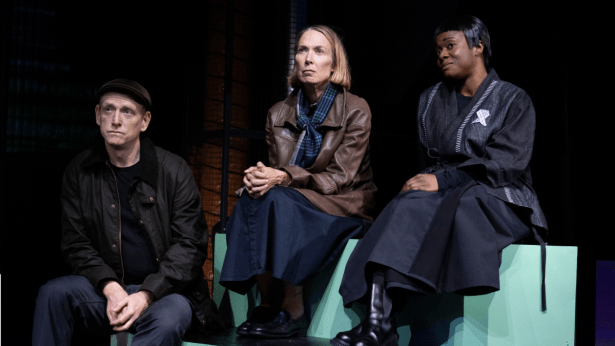

It is there that a middle-aged lawyer (Elizabeth Marvel) is summoned by a functionary for the state (Scott Shepherd) to defend a death row inmate (Elizabeth Yeoman) who has unexpectedly decided to retract her wish to be executed “without pain.” There will now need to be a trial to decide this question, with a jury of 100 algorithmically selected citizens observed by the keeper of the algo-generating Machine (Henry Stram) as well as a financier who’s funding the project and hoping to expand its operations overseas for even greater profit (Jennifer Mogbock).

As in his 2019 play Socrates, Nelson is interested in Ideas with a capital I and uses his characters as mouthpieces for a high-end discussion of issues such as justice, free will, democracy, personal responsibility, and the futility of resistance in the face of rising autocracy. The stage is set early on with a conversation between Shepherd’s Official, perky and convinced of the rightness of his assignment, and Marvel’s Lawyer, who has become disillusioned by a reformed justice system that renders her role largely meaningless. (She last won an acquittal for a client six years ago and has had no cases in over a year.)

Her idealism is reawakened when she meets her client, a young woman who’s admitted to killing her husband, two children, and mother. In an astonishing Off Broadway debut that should put her at the top of every casting agent’s list, the young Juilliard grad Elizabeth Yeoman conveys the raw horror of a woman who has been treated less as a criminal suspect than a human guinea pig — sent to an isolated prison cell only after enduring abusive scientific experimentation and a partial lobotomy by researchers hoping to study the genetic origins of the criminal mind. As a result, she flinches at the approach of other humans and spits out garbled sentences consistent with the aphasia experienced by brain trauma victims.

But there’s a kind of fridge-magnet poetry to her speech that suggests that a rational soul remains just beneath the surface. “Took more blood than had blood,” she recalls of her time as a research subject. “study you like wasp you are nurse said.” Yeoman is absolutely riveting, looking haunted and wounded while harboring a fierce determination to be understood, and ultimately to assert her autonomy despite her incarcerated circumstances. She makes a character who should be easy to dismiss or repudiate into a figure to whom we can’t help but extend some sympathy.

But the Machine sees no point in mercy — even though it twice revived her after suicide attempts. “It’s the law to revive other than in cases where the state itself does the deed,” the lawyer notes dryly. It also fails to recognize the contradiction in declaring the inmate to be not of sound mind but allowing her to waive her right to a trial. Nelson injects a good deal of Orwellian doublespeak in the exchanges over the legal case that underscore the circular logic of people pushing for tech-based reforms: “We give up meaningless freedoms for greater freedom,” “What she says is not what we hear,” a pre-ordained verdict is merely “the inconvenience of deliberation removed.”

All of these philosophical debates benefit from the evocative physical production, beginning with David Meyer’s lo-fi sci-fi set design, with its bright orange tubes and movable Erector-set-like rectangular columns, as well as Marina Graghici’s monochromatic near-future costumes, Reza Behjat’s lighting, and especially the sound and original music from Henry Nelson and Will Curry. (In one of the show’s funniest moments, as the parties in the trial enter a sidebar discussion about whether Marvel’s lawyer should be allowed to utter the name of the prisoner during the proceedings, the stage goes dark and we hear bouncy hold music for close to a minute until the trial resumes.)

Like many a writer who’s built a world on abstract ideas, Nelson doesn’t quite know where to take his fascinating premise — which leads to a short coda of a second act that’s puzzling, perfunctory, and largely unsatisfying. What’s worse, it represents a betrayal of Marvel’s heroine, the reluctant advocate for old-fashioned values of justice and logic who’s so suspicious of surrendering to technology that she wields a pen and paper notepad throughout the first act, unlike the tablet-wielding bureaucrats she’s challenging. While Nelson doesn’t stick the landing, And Then We Were No More spotlights the dangers that our justice system faces from new technologies, corporate interests, and our own passivity. ★★★★☆

AND THEN WE WERE NO MORE

La MaMa, Off Broadway

Running time: 2 hours (with 1 intermission)

Tickets on sale through November 2 for $49 to $99