Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter, who famously played stoner time travelers in the Bill & Ted comedies 35 years ago, were not high on anyone’s list to tackle the philosophizing tramps Estragon and Vladimir in Samuel Beckett’s absurdist comedy Waiting for Godot. But here they are, in a stylishly spare Broadway revival from theatrical auteur Jamie Lloyd that strips the esteemed Irish playwright’s text of any concrete sense of time and space, to mixed results.

Reeves and Winter show a comfortable camaraderie that plays on their screen personas in ways that are cunning if a bit predictable. I pity their fans who are unfamiliar with this play, or its stubbornly unconventional approach to narrative and comedic conventions. (When Winter’s Vladimir followed an extended riff on the fate of the two criminals crucified with Jesus with the line, “this is not boring you I hope,” one audience member at my performance actually shouted to the stage, “No!”) The duo does earn laughs from two direct nods to their cinematic past: a pantomimed bit of air-guitar strumming in the second act (“back to back like in the good old days”) that feels cheap and then a line that exists in Beckett’s original 1952 script but takes on a different cast in this production: “What’s the good of losing heart now, that’s what I say,” Vladimir tells his sad-sack companion. “We should have thought of it a million years ago, in the nineties.” (The first two Bill & Ted movies were released in 1989 and 1991.)

Reeves leans into his notorious deficit of affect, delivering his lines with a world-weariness that’s apt if sometimes bordering on monotonous. As the excitable chatterbox Vladimir, Winter shows a bit more dramatic range in speculating on their characters’ plight stuck in a literal no-man’s-land awaiting the arrival of the elusive Godot, whom they hope will end their days of misery and boredom and nighttime beatings by unseen antagonists.

The pair’s curmudgeonly banter is interrupted by the arrival of the bullwhip-wielding aristocrat Pozzo (a terrific Brandon J. Dirden) and his indentured servant, Lucky (Michael Patrick Thornton) — revealing different shades of humanity’s predicament that are deepened when Pozzo returns in the second act as a blind man unable to pull himself back on his feet after a fall. Despite being in a wheelchair and wearing a Hannibal Lecter-like mask most of the time, Thornton stands out with his defiant plays to the audience and his impressive delivery of Lucky’s famous monologue, a loghorreal gush of words that is both erudite and nonsensical. In addition, we meet a white hoodie-wearing boy (Eric Williams shares the role with Zaynn Arora) who turns up as a kind of angelic messenger stringing them along with shrug-filled assurances of Godot’s promised arrival… at some point.

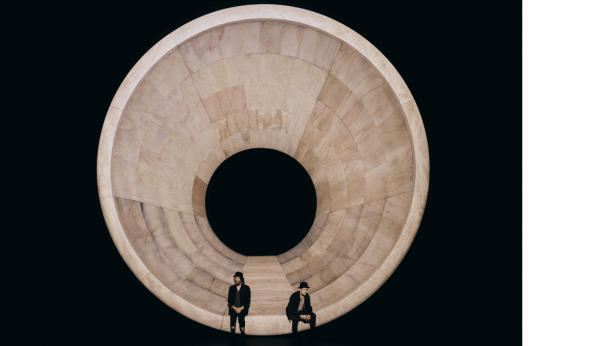

Lloyd, the auteur behind stripped-down productions of classics like the Jessica Chastain-led A Doll’s House and last season’s Andrew Lloyd Webber revival Sunset Boulevard, again works in a monochromatic palate on a monumental scale. Soutra Gilmour’s set, a giant translucent-marbled funnel that resembles a concave cornea narrowing to a distant upstage pupil, is an abstract sculptural marvel — dramatically lit by Jon Clark to suggest an installation piece by perceptual artist James Turrell. (Gilmour’s costumes range from gray to black, sometimes making the actors hard to distinguish — especially since the set design also cuts off sightlines of upstage action for audience members seated on the outer sides of the aisles. You’ll want to nab tickets closer to the center, if possible.)

What’s missing here is any specific sense of place, like the tree that’s meant to be their meeting point and is usually the most striking design feature in any Godot revival. Vladimir and Estragon point to it, off in the distance behind the audience, and we hear but do not see how it mysteriously sprouts leaves in the second act. Gone too are any props. Reeves’ Estragon bites a pantomimed carrot and chicken bone, making exaggerating chomping noises, while Pozzo cracks his imaginary whip and Lucky is described as struggling with an unwieldy pile of luggage that we never actually see. Are earthly burdens, and basic human sustenance, mere abstractions in Lloyd’s conception of the play? Why then does Estragon wrestle with his actual boots, or make a point of trading his very real bowler hat with his buddy in a bit that’s a vaudevillean highlight of many productions but here disappoints? (On the plus side, the stars’ marked difference in height does recall the duo who famously inspired Beckett: Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy.)

The departures from tradition are nothing new for Lloyd, who is fond of directorial flourishes that are often brilliant but don’t always contribute to our understanding or appreciation of the material. His Godot is no different. While Reeves and Winter lack the acting reach of recent Estragons and Vladimirs on the New York stage, they bring a certain disillusionment that seems distinctly Gen X in its sensibility. They’re not sad clowns like Bill Irwin and Nathan Lane in the 2009 revival. Or the reunited geriatric music-hall chums that Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart embodied in a 2013 production. Two years ago, Michael Shannon brought a hangdog sweetness to Estragon (opposite Paul Sparks’ Vladimir) that subverted his history of playing glowering heavies on screen. There’s nothing flashy or showy to Reeves and Winter’s performances; they project an aloofness that reminded me of latchkey kids who strayed too far before darkness set and can no longer find their way back home.

Reeves, in a striking Broadway debut, takes an approach that’s remarkably true to his persona. His Estragon recalls his slack-jawed hero from The Matrix series if Neo had refused both the red pills and the blue pills — one to see the world as it really is, and the other to live in blissful ignorance of the truth. Instead, he prefers to ponder his options and not commit to any one course of action. He and Winter create a version of Godot that works on its own terms even if fails to break out of the shadow left by more distinguished predecessors. Their tramps prefer passing the time on the outskirts of existential dread without daring to plumb its depths. That’s a shame, but at least this solid revival might introduce this challenging work to a wider audience. Beckett will survive the shortcomings of this production. Because classics, like frail humans stuck in the limbo of an existence they cannot fully comprehend, are remarkably durable. ★★★☆☆

WAITING FOR GODOT

Hudson Theatre, Broadway

Running time: 2 hours, 5 minutes (with 1 intermission)

Tickets on sale through January 4 for $134 to $593