Anna Christie has become a kind of oddball stepchild in the Eugene O’Neill canon, seldom seen in New York City since the memorable 1993 Broadway revival with Natasha Richardson and Liam Neeson. But it’s a sturdily constructed if old-fashioned four-act melodrama, and one that ends on a surprising moment of uplift. Thomas Kail’s uneven new revival at St. Ann’s Warehouse, staged with the audience on three sides and a back wall with a seascape of empty liquor bottles, reinforces both its virtues and its challenges.

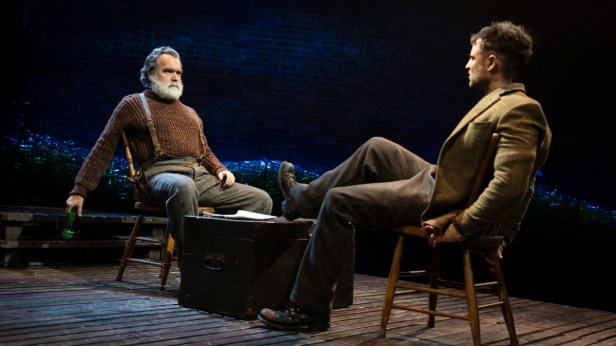

Michelle Williams stars as the title character, a 20-year-old fleeing a checkered past in the Midwest where her estranged seadog of a father fobbed her off on relatives as a young girl following the death of her mother. Brian d’Arcy James, nearly unrecognizable beneath a bushy white beard and a Nordic accent as thick as a chunky cardigan, is astonishing as the dad, Chris Christopherson, who embraces the chance to make amends for his long absence from his daughter’s life. His protectiveness — and rejection of a sea-adjacent life for Anna — only grows when she gets close to a brash Irish sailor named Mat Burke (Tom Sturridge) who’s almost instantly besotted with the young woman hiding the real reason she fled St. Paul.

Williams is a fantastic film actress, injecting subtlety and nuance into her work in Brokeback Mountain, Blue Valentine, and Manchester by the Sea. But she has faced a more difficult transition to the stage, delivering mannered performances in a 2014 revival of Cabaret and the 2016 Broadway production of Blackbird. Now she’s trying to out-Garbo Greta Garbo, who famously starred in the 1930 film adaptation of Anna Christie.

It’s not that Williams attempts to mimic the late star’s distinctive deep Swedish accent, thank heavens, but her voice seems to drift throughout the show like a boat untethered from the dock. Sometimes she attempts a Fargo-style Minnesota inflection to reflect her character’s arrival to the East Coast from St. Paul. At other times she settles into a stagey version of her contemporary voice. But she also frequently channels the rat-a-tat line readings of a citified moll from pre-code Hollywood, as if the actress has watched nothing but Turner Classic Movies in preparation for the role. (She looks stunning in Paul Tazewell’s crisp and stylish costumes, though they seem far too fancy for a woman who keeps reminding us how close she is to financial destitution.)

Williams’ approach might make sense if there was some consistency — or if her Anna feigned a cinema-inspired tough act in public and retreated back to a more natural way of speaking in private moments. Although she nails her big confesssion in the second act, conveying a sense of both fragility and endurance, there’s no rhyme or reason to her line delivery from scene to scene.

There’s also no discernible romantic chemistry with Sturridge, who at times seems to be channeling a hot-tempered Stanley Kowalski, only with a brogue that can be thicker than mashed potatoes. They both project a certain passion, but all too often it seems to be directed not at each other but outward to the audience — a performance of romance that doesn’t seem to be deeply or genuinely felt. Williams is better in her scenes with d’Arcy James and Mare Winningham, who mesmerizes in the opening scene as Chris’ lager-swilling lover whom he unceremoniously dumps to make room for Anna. Scrunching her face like an applehead doll, Winningham economically conveys the hardened resignation of a woman who’s led a difficult life and expects no better — a clear warning sign of how Anna might end up if she’s not careful.

Kail and his design team have crafted a handsome production, with sturdy seamen shifting and stacking weathered wooden pallets around the stage between scenes and a giant steel beam first used as a saloon bar and then hoisted aloft to hover over the action like a ship’s mast or a giant sword of Damocles. (Christine Jones and Brett J. Banakis are credited with the scenography, with Natasha Katz’s lighting amid the occasional onset of fog by special effects designer Jeremy Chernick.) But the attempts at symbolism seem strained for a play as straightforward and muted as this one — where the characters manage to avoid the ravages of alcoholism or shipwreck or even death by gunshot despite the appearance of a pistol late in the show.

Anna Christie remains a curiosity — but one that deserves a warmer, more thoughtful embrace than it gets here. ★★★☆☆

ANNA CHRISTIE

St. Ann’s Warehouse, Off Broadway

Running time: 2 hours, 30 minutes (with 1 intermission)

Tickets on sale through February 1 for $59 to $199