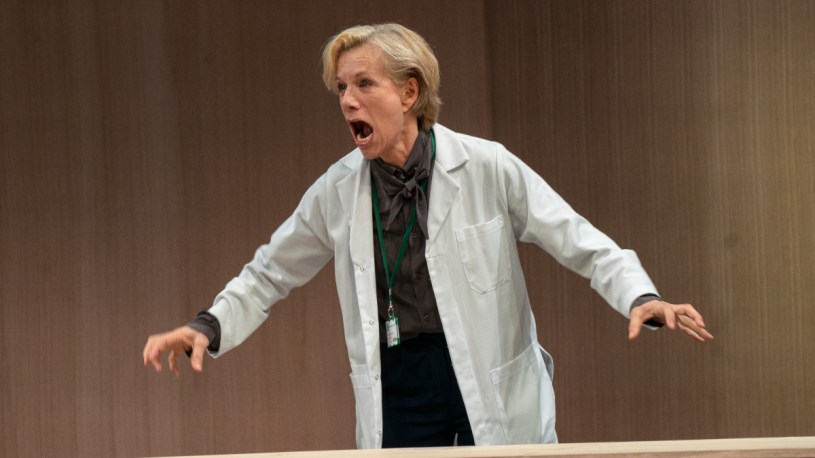

The brilliant British dramatist-director Robert Icke returns to the Park Avenue Armory with an updated version of Austrian playwright Arthur Schnitzler’s timely and prescient 1912 drama Professor Bernhardi, here renamed The Doctor and starring Juliet Stevenson in a performance that is both fiery and philosophical. The gist of Schnitzler’s original drama remains: A Jewish physician causes a public uproar after refusing to allow a Catholic priest to perform last rites on a teenage girl who is dying of sepsis following an abortion, hoping to prevent any trauma for the patient — who is unaware of the severity of her condition.

Icke expands on the confrontation — which includes some brief physical contact between the doctor and the priest as she blocks the door of the patient’s room — to make it a kind of Rashomon for the modern age of identity politics and cancel culture. Stevenson’s Ruth Wolff faces not only anti-Semitism but also misogyny — as well as a bit of anti-intellectualism in her somewhat naive defense of meritocracy at all costs. (She refuses a suggestion to hire a Christian doctor for an open position at her clinic, to tamp down the controversy, instead favoring a Jewish woman she considers better qualified.) And when it emerges that the priest is Black, cries of racism color the public response to the case as well. (Icke tosses in subplots about lesbianism and gender identity as well, in the apparent belief that his kitchen-sink drama could use a few more dirty dishes.)

The identity politics of the plot are upended by Icke’s casting choices — the Black priest is played by a white actor (John Mackay) while Wolff’s antisemitic, misogynist colleague is played by a woman (Naomi Wirthner). Other roles are similarly cast without regard to race or gender, forcing us to listen closely to parse the details about these characters that are relevant to the arguments they are making.

In Icke’s version, the trial that Wolff faces is not a criminal one — but rather a public excoriation on a public-interest TV show where she faces down the questioning of five panelists representing five different, increasingly hostile points of view on the case, from devout Christians to self-proclaimed “woke” activists to medical ethicists. The arguments can be silly (“Christian patients need Christian doctors”) but the cumulative effect is overwhelming. Our heroine doesn’t stand a chance.

Wolff is felled by her hubris, a devotion to the principles of science and medicine that is every bit as unyielding as those she condemns for an equally strident devotion to religious faith. But her comeuppance feels out of proportion to her supposed sins. Icke seems to dismiss the antisemitic, misogynistic and anti-science attacks on her — even forcing her into a quasi-confession with the priest toward the end of the play, when she is at her lowest moment and reeling from how quickly her successful career unraveled. It’s a humiliating, and frankly unconvincing end.