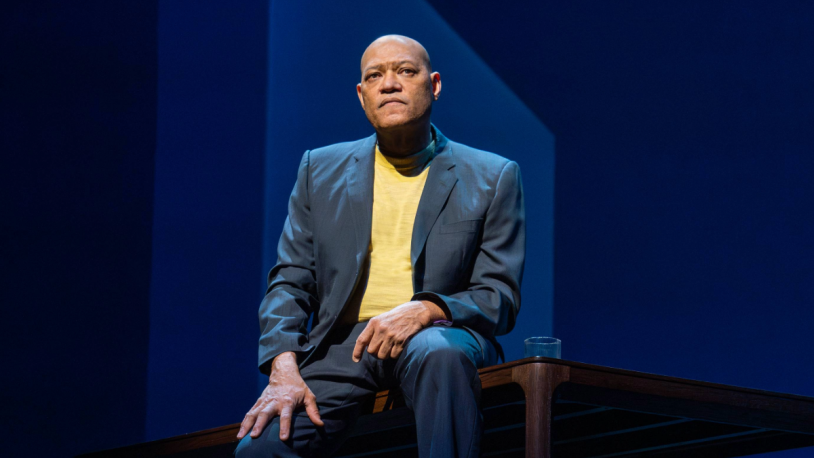

Laurence Fishburne has been a movie star since age 11, when he appeared in the 1975 drama Cornbread, Earl and Me. He’s had a storied career ever since, earning Emmy and Tony awards, and standing out signature movies like Apocalypse Now, Boyz n the Hood, and the Matrix and John Wick franchises. In his solo stage show Like They Do in the Movies, which opened at PAC NYC on Thursday, he treats audiences to two productions in one.

The more compelling show, which bookends a performance that lasts just over two and a half hours (with an intermission), involves Fishburne recounting stories of his complicated upbringing in New York City and Augusta, Georgia, and the influence of two domineering grandmothers as well as parents who did not live together but did the best they could to nurture young Larry. Fishburne is a compelling narrator of his life story whose matter-of-fact approach to episodes of horrific trauma helps to smooth the audience’s shock — and to explain how Fishburne both distanced himself from his parents but also reinserted himself in their lives when their health declined in their later years.

Between these chapters, though, Fishburne inserts five overlong scenes that he lumps under the broad category of “everybody’s got a story.” Unlike with his autobiographical vignettes, he launches into these segments abruptly and without introduction. We meet an Italian American pressman for a New York tabloid who uses his connections with the cops after he’s arrested on the subway; an ex-cop and ex-con now working security on film sets (and knitting a sweater); a homeless guy full of patter about all the A-listers whose cars he’s squeegeed; and an American expat running an Australian brothel and willing to share his own wife with a client. These scenes are showcases for Fishburne’s chameleonic gifts as a performer, allowing him to adopt wildly different accents and mannerisms in monologues that are smartly written to reveal the characters’ backstories in naturalistic ways.

Alas, these character sketches also tend to burrow into digressions and narrative cul-de-sacs to that they eventually overstay their welcome. One wishes that director Leonard Foglia had prevailed on Fishburne to trim down the script. (These scenes also sometimes seem to be a challenge for the actor, who four times at my performance received an audible prompt for his next lines.)

These non-Fishburne monologues are confusing for a number of reasons. Because he has told us in the opening minutes that his material is sometimes true, sometimes fiction, and sometimes a mix, it’s difficult to process a long, moving account of the horrors of Hurricane Katrina for a physician and her husband who were stuck for nearly a week in a storm-ravaged New Orleans hospital. Are all the ghastly details true? Or merely “true” in some emotional or moral sense? And what connection does this story have to Fishburne himself, a man who gleefully admits his delight in “talking shit and telling lies for more than 50 years”?

Fishburne is on surer ground when he returns to his personal story, particularly when he conjures a touching portrait of his aged mother, blind and suffering from dementia, as the two forge a kind of reconciliation following years of estrangement. She squats at the edge of the stage and looks up at her nursing-home visitor, sometimes mistaking her son for Fishburne’s father or grandfather or for another man from her diverse romantic past. And she squints up into the spotlight with a vulnerability that seems hauntingly uncharacteristic of the bulldozer of a woman who’s been described to us all evening. It’s a moment of compassion — and of grace — that’s all too rare in theater and in life.