Tamara de Lempicka, a Polish-born painter whose Art Deco paintings of aristocrats and stylish nude figures achieved cult status particularly after her death in 1980, lived a long and colorful life worth telling. But the creators of Lempicka, a long-gestating original musical that opened Sunday at the Longacre Theatre, seem a bit flummoxed about what version of the artist’s story they want to tell beyond giving their star, Eden Espinosa, a series of mostly indistinguishable power ballads.

Is she the ultimate survivor, the daughter of a Jewish father who overcame antisemitism in Russia and Paris before escaping to the United States ahead of the Nazi occupation of France? Is she a queer icon who pursued a lusty relationship with a lower-class woman (the radiant Amber Iman) while still married to an aristocratic husband with claims to Polish royalty (Andrew Samonsky, with the voice, look and stiffness of a Disney prince)? Is she a pioneering artist who embraced the post-Impressionism monumentalism of her era with Cubist-inflected Art Deco designs? In the hands of composer Matt Gould and lyricist Carson Kreitzer (who co-wrote the book), she’s an amorphous survivor who begs for a sharper characterization.

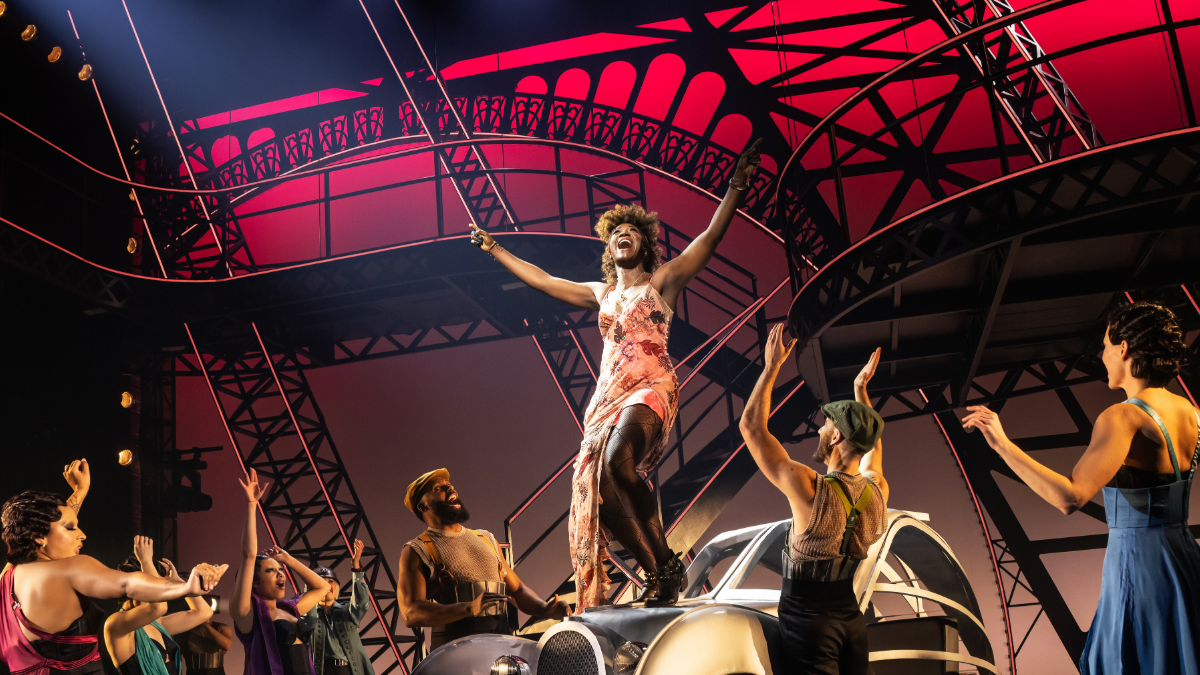

The gifted singer Eden Espinosa, wearing a blond wig and gorgeous costumes (by Paloma Young), is as flat as one of Lempicka’s canvases in the role, a figure who emerges as more of a passive observer of her life story than the active driver of the plot, particularly in the second act. In her opening number, set in 1975 Los Angeles, an older Lempicka declares, “History’s a bitch but so am I.” Would that that were true, that we had seen a woman as fierce and uncompromising and sharp-edged as the often half-clothed figures in one of Lempicka’s better known paintings (which pop up in Peter Nigrini’s projections on Riccardo Harnández’s loosely Eiffel Tower-ish set).

Iman, blessed with the score’s broadest range of songs, from blues to torch songs, runs away with the production. Her mesmerizing look and no-nonsense attitude convince you why she might be the ultimate muse for a young artist grappling for her signature style. (Never mind that like many of the show’s characters, she seems to be a mostly fictionalized amalgam.) And she also nails the show’s best number, a duet not with Espinosa’s Lempicka but with the husband, “I Can See What She Sees in You.” As the two romantic rivals size each other up, Iman delivers a series of gorgeous harmonic runs as Samonsky sustains one long note.

But not only do we never really understand what Iman’s Rafaela sees in Tamara (she flatly refuses a jewel-bedecked bracelet so avarice isn’t a motivation), but the show’s focus keeps shifting to other characters, none of whom is any more fleshed out. We meet Tamara’s bratty daughter (Zoe Glick), apparently resentful that she’s been replaced as her mother’s go-to model, a bawdy lesbian bar proprietor (Natalie Joy Johnson), who spouts anachronistically witty asides, a baron and his wife (Nathaniel Stempley and Beth Leavel), who pop up occasionally to purchase art and offer life advice. Leavel’s baroness even nabs the 11 o’clock number, a wistful you-must-go-on anthem that comes out of nowhere and fades just as quickly from memory.

There’s also an elder artist/mentor named Marinetti (George Abud), based on a real Italian poet-artist who was friends with Lempicka — though not one of her early instructors when she was getting her start in Paris. He’s an advocate of the so-called Futurist school, a proto-fascist movement that sought to supplant patron-driven, portrait-focused art for a more egalitarian aesthetic that championed the power of machines and industry. Here, he’s also burdened with delivering much of this historical backstory of a show that unfolds mostly between the Russian Revolution and the onset of World War II, in loud, talky songs that borrow heavily from Evita-era Andrew Lloyd Webber.

These production numbers are not only loud but busy, with the large chorus summoned to execute Raja Feather Kelly’s dull and derivative choreography. Despite the 1920s and ’30s setting, the group movements owe less to the flapperish Jazz Era than to 1980s workout tapes and music videos. (Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation” is a clear influence in an Act 2 number celebrating the dawn of the Industrial Age.) Director Rachel Chavkin keeps the show moving, summoning a lot of commendable stage craft to make up for gaping holes in the storytelling. But there’s no disguising that this is a messy show with a talented but ultimately too enigmatic character at its center. Espinosa is given several songs, including a recurring tune that is nakedly derivative of “Color and Light” from Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park With George, but none of them manage to fill in the broad brushstrokes of a woman, a lover, or a great (and underappreciated) artist.