Amy Herzog’s Mary Jane is a character study of an extraordinary woman — the single mother of a 2-and-a-half-year-old son with cerebral palsy — that resists every temptation to veer into sentimentality or histrionics. In a compelling Broadway debut, Rachel McAdams reinforces the virtues of Herzog’s characteristic understatement in a skillful production that opened Tuesday at Broadway’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre.

Director Anne Kauffman’s production emerges as a sharply observed character study of a woman who faces her day-to-day ordeal with a forthright, almost chipper attitude — and who would shrug off the label “heroic” it it were uttered in her presence. McAdams seems almost disconcertingly perky for much of the show, an attitude that seems to be more of a projection than a reflection of her actual feelings. (Carrie Coon had an easier time suggesting the character’s just-beneath-the-surface limitations in the smaller space of Off Broadway’s New York Theatre Workshop, where the show had a successful run in 2017.)

Herzog is a naturalist, an approach to storytelling she deploys here not in the service of plot but in the gradual revelation of Mary Jane as a character. We learn only gradually about her offstage son Alex’s medical condition, what has happened to Alex’s father, and how she manages to hold a job (barely, and then not at all) despite ill-timed medical emergencies — the exposition that most playwrights would be tempted to unload upfront before getting to the meat of the story.

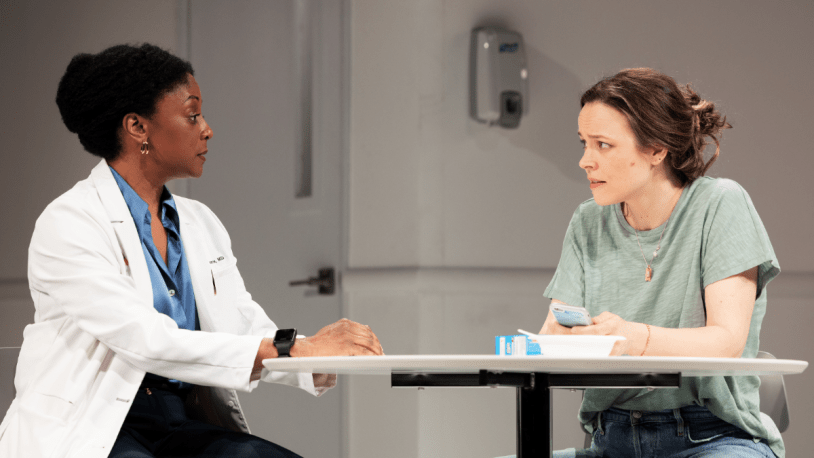

Instead, the particulars of Mary Jane’s predicament emerge gradually — and the accumulated force of them builds as a compelling substitute for onstage incident, packing quite a wallop by the play’s oblique ending. McAdams is joined on stage by four other performers, notably all female: Brenda Wehle as a superintendent and hospital chaplain; Lily Santiago as a college student and music therapist; Susan Pourfar as two mothers who have children with similar chronic illnesses but considerably more economic means; and April Mathis, who makes a striking impression as a sympathetic home-care nurse and a somewhat reserved doctor who praises Mary Jane for “advocating for your kid.”

Well into the drama, Lael Jellinek’s set shifts dramatically and the prospect of returning to a familiar home setting, however imperfect, becomes tantalizingly out of reach. We also begin to see more chinks in McAdams’s facade, though her shortness with a hospital staffer shows almost saintly restraint. As Mary Jane is pushed to the edge of her abilities with no easy answers, her conversations take a deeper, more philosophical turn. But no dramatic epiphany awaits. Trapped in a situation outside her control, she can only cling to the practical, to the concrete, to the primal instinct to protect her child no matter what. Mary Jane is unfussy naturalism that sneaks up on you with a pregnant power.