The title of Moisés Kaufman’s remarkable new drama, Here There Are Blueberries, is taken from the caption in a photo album that resurfaced in the mid-2000s showing a group of young women enjoying bowls of blueberries together with their boss. The banality of the image becomes more complicated when you understand the context — these women, some just teenagers, were Nazi communications workers at the Auschwitz concentration camp in Nazi-occupied Poland in the 1940s. And the album of 100-some similarly benign snapshots belonged to a Nazi officer, Karl Hoecker, a former bank clerk who became the administrative assistant to that notorious death camp’s head, Rudolph Höss.

Kaufman, who conceived and directed the show and co-wrote it with Amanda Gronich, forces us to confront some fundamental questions about human nature — how we are capable of great harm, how we compartmentalize our lives to mitigate our sense of responsibility (and guilt) for collective actions, and even how we cling to mementos of a past that is not always pretty or depict us in the best light. The photo album that surfaces does not contain the single image of an Auschwitz prisoner, but their absence makes the photos all the more haunting. And it forces us to confront the fact that hiding the obvious from view does not make it go away.

Here There Are Blueberries, which opened Monday at Off Broadway’s New York Theatre Workshop after being named a finalist for this year’s Pulitzer Prize in Drama, bears remarkable similarities to the recent Oscar winner The Zone of Interest, which depicted the life of Höss and his family as well as the other Nazi officers at Auschwitz as they went about their daily lives while blithely blocking out the horrors that were unfolding just over the back wall of their garden. (Some of the physical details in the film seem to be lifted from the photos in Hoecker’s album.)

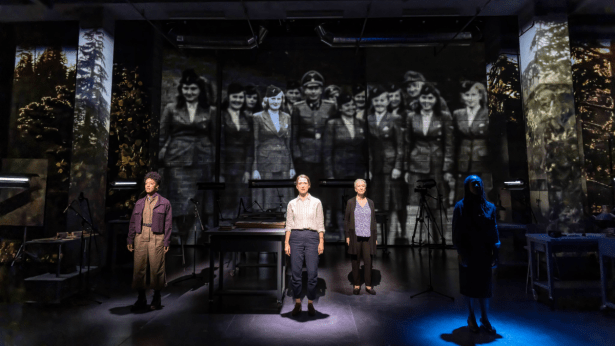

Kaufman and Gronich’s script is artfully constructed as a kind of academic investigation, with archival researchers at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum elevated to the role of bookish Sherlock Holmeses or more sedate versions of Dan Brown’s Robert Landon. The physical production underscores the heroic efforts of researchers — from Derek McLane’s versatile set design, with archivist desks that could double as religious altars, to David Lander’s epic lighting to David Benali’s projections, which artfully spotlight the actual photos being discussed.

The play leans on the text of actual documents and letters that they unearth in their quest to identify the people in the images and to puzzle out the meaning of the images. In an image of Hoecker flirtatiously posing with the young women on the communications team, we can zoom in on his hand and the wedding ring he wears. There are scenes of Christmas trees being decorated in December 1944, just weeks before the Soviets raided the camp. Did they not realize the Nazi effort was failing, or think to send their children away?

More shockingly, we see a celebratory photo featuring scores of uniformed officers, with Höss and notorious “Angel of Death” Holocaust architect Josef Mengele standing up front, as a man plays an accordion before them. What could they be celebrating? We learn that the image contains some documentary clues to date the image to July 1944 — when the Nazis completed the extermination of 350,000 Jews forcibly removed from Hungary that spring.

To their credit, Kaufman and Gronich help us to understand the mentality of these Nazi flunkies without ever letting them off the hook completely. We hear from Holocaust historian Stefan Hördler: “The women think, ‘Oh we just make phone calls, we don’t handle prisoners.’ The SS doctors think, ‘We just select if they’re fit or unfit for work.’ Even the guy who takes people into the gas chamber says, ‘I didn’t select them.’ And everyone thinks, ‘If I didn’t do it, someone else would have.’ No one feels responsible.” It’s an alarmingly ingenious system for shirking individual responsibility — and it presages how easily seemingly ordinary, supposedly upright people can get caught up in situations whose deadly-serious meaning they may only comprehend in retrospect, if at all.

Elizabeth Stahlmann leads the superlative eight-person cast, each of whom shifts among multiple roles throughout the 90-minute performance and presents the material with understated calm. It would be easy to oversell the drama, to offer a maudlin tug at our emotions. But Kaufman’s more methodical and restrained approach, calmly laying out the facts as the researchers piece together new information, produces an even greater wallop in the end. We can no longer look away, or hold history at arm’s length. We are all implicated in the atrocities committed around us.