Sometimes it takes outsiders to bring a fresh perspective to familiar material. Dark Noon, which opened Monday at Brooklyn’s St. Ann’s Warehouse following acclaimed productions in Europe, seeks to dismantle the ideology and underlying biases of classic Western films that were a staple in South Africa where much of the seven-member troupe grew up.

Danish writer-director Tue Biering (who co-directed with choreographer Nhlanhla Mahlangu) seeks to upend the genre by casting a 21st-century eye on familiar beats in the history of European settlement of the American West. We meet struggling prairie farmers, Civil War veterans who become hired cowboys for larger ranches, Chinese immigrants conscripted into building the railroad, sex workers who were among the first female settlers (and entrepreneurs), and a parade of other characters representing the contradictory impulses toward violence and civilization that marked the period.

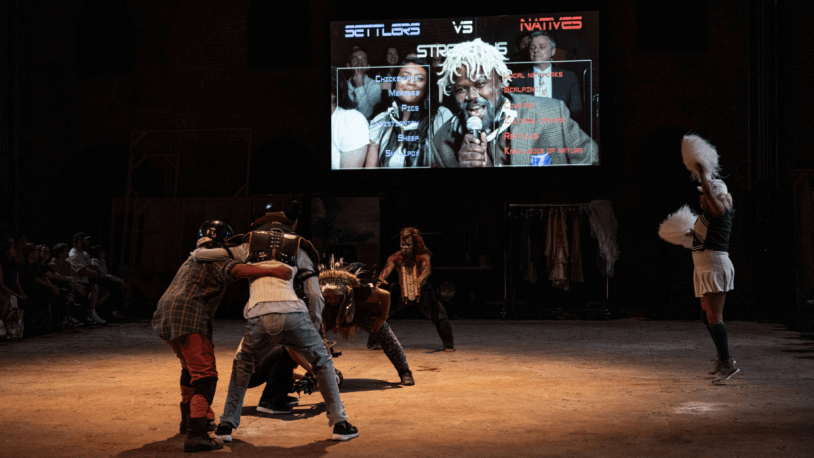

What makes Dark Noon such a rollicking entertainment, though, is Biering’s embrace of 21st-century technology as well as modern devices like audience participation that turn material that could easily have become a kind of ultra-serious TED talk for the woke into something much more engaging and ultimately moving. There’s a sense of playfulness here, and humor, that is apparent from the start when an actor rolls like a tumbleweed across the barren prairielike playing area (designed by Johan Kølkjær). The mostly Black cast don outrageous blond wigs, and even slap on whiteface, to underscore the distance from the characters they are playing. The show also leans heavily on live video, with cameras set up in strategic places and projected onto the back wall of the theater. The battle between white settlers and native peoples is depicted as a sporting competition, with a play-by-play commentator marking the action from the front row and a scoreboard included on that back-wall screen.

Before long, the vast open performing space becomes crowded with simple stand-up frames: a house, saloon, church, general store, bank, prison, and even a rolling dolly on railroad tracks down the middle. (That screen on the far wall may be the best way for some theatergoers on the long sides of the thrust stage to see all the action.) And we follow the history of white settlement as each of these new elements comes into play, bringing with it both the promise of progress as well as some often unintended side effects. Time and again, the troupe draws audience members into the action — at one point even putting some up for auction as slaves.

Dark Noon is an act of education, or re-education, but it also adopts an audience-first approach that is neither preachy nor distancing. The first-rate cast, who seemlessly shift among multiple roles, works with clocklike precision (even placing the cameras in just the right place to capture striking tableaux minutes later). The very style of the play not only incorporates the audience into the storytelling, but implicates us as well. We cannot remain passive observers to our own history. And just as this troupe piles white powder on their faces and layers of artifice around the narrative, we are forced to confront the ways that we are all too willing to gloss over or explain away the deficiencies of the American story.