Tony winner Norbert Leo Butz may be the biggest name in Erika Sheffer’s new drama Vladimir, which opened Tuesday at Off Broadway’s Manhattan Theatre Club, but the timely play belongs to Francesca Faridany, who brings a confident hauteur to the role of a crusading Russian journalist in turn-of-the-21st-century Russia. Faridnay’s Raya is uncompromising in just about all aspects of her life, from her eagerness to report at the frontlines of the Chechen war to her willingness to expose the human-rights abuses of the Russian military in that conflict — even as Vladimir Putin assumes control and the tolerance for a free and fair press is dissipating as quickly as the vodka supplies during the New Year’s holiday.

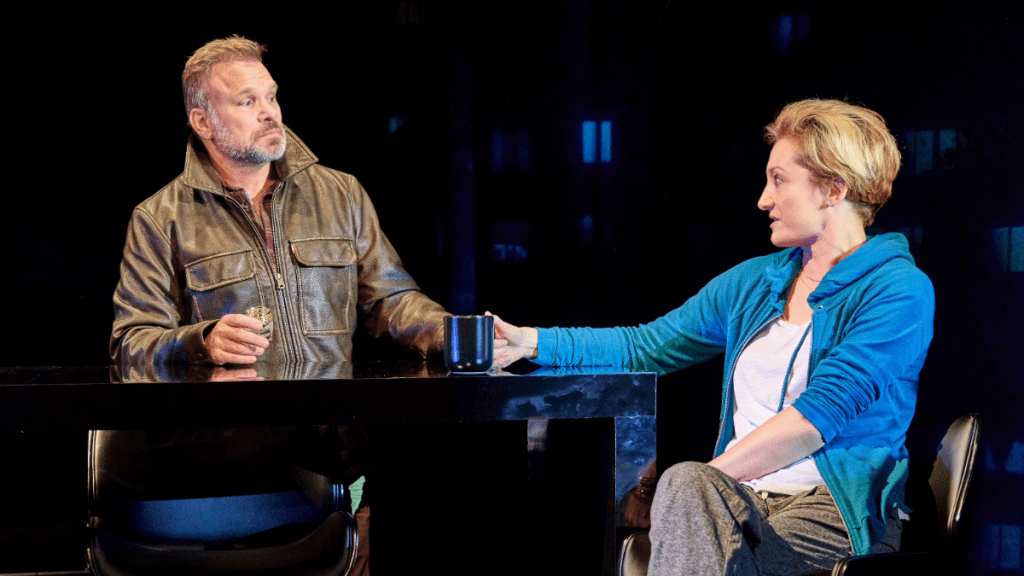

Butz plays her heavy-drinking, perpetually single boss, who’s constantly warning Raya to watch her back, particularly after he ditches the independent newspaper where they both work for a safer gig at a state-owned television station that’s under the thumb of an old college pal and now top Kremlin official (Erik Jensen). She gets similar appeals from her grown daughter, Galina (Olivia Deren Nikkanen), particularly when mom plans another reporting trek to Chechnya weeks before her wedding. Raya’s drive to expose the truth at all cost is taken to a new level when she learns of an American investment firm that was unwittingly used as a kind of money laundering operation for top Russian officials. She meets with the firm’s Ukrainian-born accountant (David Rosenberg, nicely nebbishy) and persuades him to slip her incriminating documents in a series of conversations that play on his guilt and desire to make a difference.

Faridnay cuts a striking figure as Raya, who is loosely based on the real-life investigative reporter and activist Anna Politkovskaya, who was shot to death in 2006 two years after surviving a poisoning attempt. But while we see flashbacks and hallucinatory conversations with a Chechen woman (Erin Darke) who becomes radicalized against the Russian regime, scenes that provide underscore how giving a voice to the Chechen minority also emboldens acts of terrorism, Raya remains a cipher. We never understood what motivated her to pursue this line of work, or to keep going in the face of so many pointed threats. The closest we come is in a late scene where she invokes an old Russian saying to explain why she rejects self-imposed exile: “Where you are born, this where you are useful.” But this gets us no closer to understanding why she’s drawn to this particular form of utility, at such great risk to herself and those around her.

The play ends before we see Raya’s assassination, though the tragic outcome of her persistence hangs heavily in the air. Sheffer also protects us from the fate of Raya’s accountant-source, who appears to be based on the tax auditor for an American firm, Sergei Magnitsky, who was tortured and beaten to death in 2009. (In a bitter irony, he was later convicted of tax evasion himself in a posthumous trial that inspired passage of the Magnitsky Act, which authorizes the U.S. and other governments to freeze assets and deny entry to individuals determined to be human rights abusers.) It’s a pity that the Magnitsky-like character’s boss (Jonathan Walker), inspired by the real-life Bill Browder, is here depicted as a brash American cowboy who has an affair with his secretary and quickly caves to Russian authorities when it becomes clear how high up the ranks the conspiracy runs and how precarious it is for any foreign business to continue operating under Putin. (Browder, an American-born financier was convicted of tax evasion in absentia and remains a target of interest by Russian authorities.)

Under Daniel Sullivan’s efficient direction, there are no lulls as we shift from scene to scene even as most of the seven-member cast shift seamlessly among multiple parts. The gridlike set, designed by Mark Wendland and lit by Japhy Weideman, suggests a darkened TV studio (with projections by Lucy Mackinnon) — a curious choice for a play that’s mostly about print journalists. The set’s interior walls also restrict the action to a compressed center section that is meant to replicate an apartment, a restaurant, an office, and a Chechen bus station. The sense of claustrophobia might be thematic if the show had begun with a more open stage and we saw the walls closing in on our heroine, but instead we get a visual design that feels more cluttered than clarifying.

The overall effect of Sheffer’s play has a similar feel. She packs in a lot of plot, sketches characters with admirable detail and a casual confidence, and our engagement never flags over the course of nearly two and a half hours. And after enduring so many plays over the years that have portrayed journalists as a venal and unscrupulous lot (from MJ: The Musical to the Murdoch empire drama Corruption to the recent McNeal), it’s bracing to see the profession valorized in a work of almost unadulterated hagiography. Still, I found myself hoping for a moment that would crystallize what we are meant to learn from this slow-motion horror story, besides an admiration for the sometimes foolhardy risks that some journalists are willing to take to expose the truth. Why would anyone risk their life, to reject escape into exile, to speak truth to a power that would just as soon snap their necks as admit wrongdoing? That’s a central mystery that Vladimir never satisfyingly resolves.

VLADIMIR

Manhattan Theatre Club Stage 1, Off Broadway

Running time: 2 hours, 20 minutes (1 intermission)

Tickets on sale through Nov. 10