There may come a day, in the not too distant future, when artificial intelligence will create new works of theater. But not yet, thank heavens. Jordan Harrison, whose acclaimed 2014 play Marjorie Prime revolved around an eightysomething woman with dementia and her interactions with an AI-boosted hologram of her late husband, returns to similar themes in his fascinating and timely new drama, The Antiquities, which opened Tuesday at Off Broadway’s Playwrights Horizons in a co-production with the Vineyard Theatre and Chicago’s Goodman Theatre.

The full title of this remarkable, thought-provoking show — A Tour of the Permanent Collection in the Museum of Late Human Antiquities — tips us off to the bleakness of Harrison’s vision for humanity’s ability to survive the current technological revolution. It also clues us into the buttoned-up formality of his approach to the subject matter, which is built on a series of about two dozen scenes that proceed chronologically from the early 19th century through 2240, and then reverse direction so that we revisit the same characters and settings from a new perspective.

We first meet Mary Shelley (Kristen Sieh), whose novel Frankenstein offers both a blueprint and a cautionary tale of how man’s ambition to create life and achieve immortality can lead to disastrous consequences, along with her stepsister Claire (Amelia Workman). She’s on the verge of writing that book, and we see her as she mourns the loss of her infant child and bristles at the condescension of her husband, Percy (Ryan Spahn), and his literary pals, including Claire’s baby-daddy, Lord Byron (Marchánt Davis). We then hop through time, from the dawn of the Industrial Revolution through the invention of robots and personal computers and the Internet.

Along the way, we meet a pioneering gay engineer (Spahn again) who dies of AIDS, a group of tech bros trying to choose the right voice for a Siri-like vocal software, and an actress in the near-future (Layan Elwazani) who’s struggling to compete with CGI performers and therefore gets a nose job to look more like a pre-Dirty Dancing Jennifer Grey (“Faces. Scars. Acne. A schnoz,” she explains. “What can we do that a digital actor can’t?”)

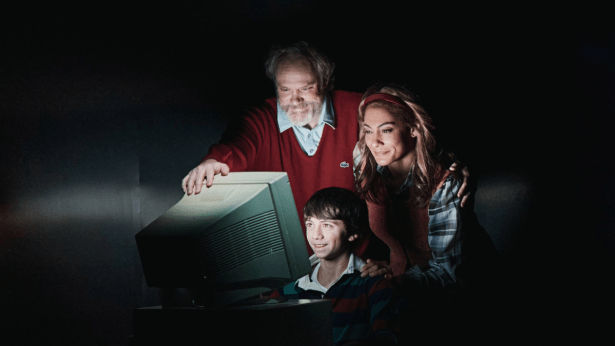

Some of the vignettes are played for laughs — a family gathers around a home computer like cavemen around a campfire, waiting for what seems like a lifetime for their dial-up internet connection to crackle to completion — while others take a more serious turn, as with a Chinese American immigrant (Cindy Cheung) meeting with her daughter’s college classmates after a car accident claims her life. The sense of foreboding increases as we head deeper into a future where the technology we’ve created seems all too eager to turn on its creators, just as Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein discovered centuries ago.

It all culminates in a scene in which a collection of props from each of the vignettes — a cellphone, a computer, a teddy bear, a butter churn — is lit up in a museum display as a voiceover puzzles aloud over their significance. What will future AI archeologists make of the artifacts of our existence? “Much of human life seemingly existed in the chasm of accident between a Zero and a One,” the voice intones from the perspective of a program built on binary coding. “Gazing upon these mute objects, we try to imagine the life that took place in between.”

And indeed, that is Harrison’s intention as well: to imagine the lived experience of humanity in the space between Yes and No, between the technological achievements that have upended our lives, both for good and for ill. It’s a fascinating exercise, especially since so much of our education and media systems have indoctrinated us into the notion that all innovations are good, or at the very least benign.

The cast of nine, expertly directed by David Cromer and Caitlin Sullivan, shifts seamlessly among the multiple characters and settings, all rendered simply but effectively on Paul Steinberg’s ever-changing set (strikingly lit by Tyler Micoleau). There isn’t a weak link here. While some scenes work better than others, particularly in the second half where there’s less need for establishing exposition, even the less compelling vignettes never last very long. (One sign of the youth of the creative team: A character in the 1970s attempts to dial a rotary phone while the handset is still cradled on the phone; old-timers will know that he needs to pick it up and wait for a dial tone first.)

My biggest reservation about The Antiquities is how the tidy, schematic nature of its construction sometimes undercuts its power, and even works against its overarching pro-humanity message. By introducing so many characters, and so many different situations, we never get to know anyone very deeply or to develop a genuine concern for their well-being — or ultimately for ours. And by setting up a strict pattern of chronological (and then reverse-chronological) sequences, the play has an almost machinelike quality that can feel constricting. It’s as if Harrison is so bound to the artifice of his play that he can’t consider the possibility of a little deviation, a nod to the way that human experience can be messy. Messy and contradictory in ways that no machine learning has (yet) been able to replicate. ★★★☆☆

THE ANTIQUITIES

Playwrights Horizons, Off Broadway

Running time: 90 minutes (no intermission)

Tickets on sale through February 23 (top price: $102.50)