Henry V, a.k.a. Prince Hal, may be the original nepo baby, a ne’er-do-well whose profligate, hard-partying ways are a source of irritation to his father, Henry IV, and who finds a more welcoming paternal figure in the quick-witted spendthrift John Falstaff marked by laziness, affability, and an inclination to skirt the law to get ahead. What will it take for Hal to grow up and prove himself worthy of the throne? That’s the central narrative arc of William Shakespeare’s Henry IV, which gets a rollicking treatment in a new production at Brooklyn’s Theatre for a New Audience under the perceptive direction of Eric Tucker (whose work with the Bedlam troupe has proven his bona fides bringing fresh life to traditional scripts).

The veteran actor and writer Dakin Matthews has nearly halved Shakespeare’s original text — typically presented as a two-play epic — into a well-paced drama that unfolds over three hours and 45 minutes (with two intermissions) and marks the stages of Hal’s evolution from rabble-rousing party boy to a serious warrior prince eager to prove his worthiness for royal duties. It’s the story of fathers and sons, and the inevitable tensions that emerge between young men and the elders they seek out for both guidance and affirmation.

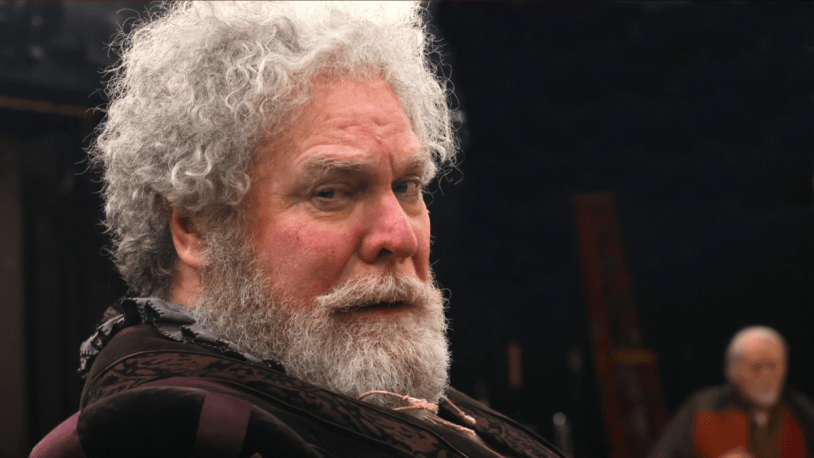

Matthews also brings a wizened snappishness as the elder Henry, who’s more of a secondary character in the play that bears his name (he gets a meatier role in the Bard’s Richard II, which follows Henry’s successful rebellion against Richard to usurp the English throne). Now nearing the end of his tenuous reign over early-15th-century England, Henry is barely able to contain his irritation with Hal (“dishonor stains the brow of my Harry,” he admits) even as the younger man begins to shed his dissolute past and step into leadership. Matthews’s Henry is the portrait of a monarch in twilight, recognizing the unlikelihood that he’ll pull off ambitions like a long-desired pilgrimage to the Holy Land amid the ongoing threat of rebellion from land-owning aristocrats from northern England, Scotland, and Wales.

Henry’s dismissive attitude toward his son explains why Hal (smartly played by Elijah Jones as a young man in transition) initially seems so lost, palling around with his buddy Poins (Jordan Bellow, who also plays Hal’s brother, Prince John) in a joking manner that suggests bros who’ve just stepped off the set of a ’70s sitcom. Again and again, he seems drawn to the magnetic charms of perennial barfly John Falstaff, played with an impish, bacchanalian flourish by Jay O. Sanders. Falstaff is a quick-witted layabout with a gift for trash-talking and yarn-spinning that’s matched only by his ability to shirk actual responsibility (or pay off his considerable bar tab). Hal has a soft spot for Falstaff — pranking him and verbally sparring with him with real affection — until he recognizes the older man’s inability to evolve into a more responsible version of himself as Hal himself is nudged into doing.

It’s a treat to see the journey that Jones’s Hal undergoes over the course of the play, and the ways that the actor injects some lines with the cadence of a Black preacher at the pulpit to signal his capacity for seriousness even amidst his sowing-wild-oats stage of life. His laid-back reluctance to accept a leadership role stands in contrast with Harry Percy (a riveting James Udom), the brash young leader of the rebel forces seeking to depose Henry. Early on, the old king admits that he admires Percy for his gallantry and military prowess (especially in contrast to his own son). Udom injects Percy with a hot-tempered relentlessness, pacing the tiny in-the-round stage and working himself up over slights both real and exaggerated. In a nice touch, the actor even leans over a theatergoer in the front row as he speaks of his promise to creep up on King Henry in his sleep “and in his ear I’ll holla ‘Mortimer!'” — a pointed reminder of Henry’s reneging on a deal involving Percy’s brother-in-law Edmund Mortimer (Elan Zafir).

Despite the simplicity of the staging — a minimalist set by Jimmy Stubbs, costumes by Catherine Zuber and AC Gottlieb that hint at the period while also suggest hoodie-forward modern garb — Tucker introduces a series of smart ideas to help reframe and update the story. The second act, which centers on the battlefield confrontation between Percy and Hal (as well as both its run-up and immediate aftermath), is treated as a kind of prize boxing match, with low-hanging overhead lights and the chimelike tolling of a bell between individual scenes. The lighting, by Nicole E. Lang, goes horror-film red during the actual clash of swords.

The cast, which frequently doubles and even triples up on roles, is superb. Standouts include Cara Ricketts, who shows different shades of fierceness as Lady Percy and the sly sex worker Doll Tearsheet; John Keating as the Earl of Westoreland and Robert Shallow, a hilariously pompous landowner who gets caught up in one of Falstaff’s schemes; and the scene-stealing Steven Epp as the rebel Earl of Worcester, the excitable barman-turned-page Francis, and the gluttonous Silence.

In the end, though, it is Sanders’s Falstaff who holds our attention as a man who’s been a fun-loving free spirit so long that he fails to recognize that many of his pals and patrons have grown up and settled down — chief among them Hal, whose final dressing down (“Fall to thy prayers; how ill white hairs become a fool and jester”) registers on Sanders’s face as a kind of body blow. Not that Falstaff can remain depleted for long. This is a man who seeks no honor in risking his life for a cause, only in surviving, and who always seems to land on his feet. And so, just moments after he has been banished from the new king’s court, he is trying to spin even this misfortune to his advantage. In Shakespeare, as in life, you can’t keep a lovable rogue down. At least not for good. ★★★★☆

HENRY IV

Theater for a New Audience, Brooklyn

Running time: 3 hours, 45 minutes (2 intermissions)

Tickets on sale through March 2 (standard tickets: $102 to $132)