Lights Out: Nat King Cole, a weirdly structured biomusical about the late, great jazz singer that opened Tuesday at the New York Theatre Workshop, is a curious exercise in polarities. The brainchild of actor Colman Domingo and director Patricia McGregor (who assumes those duties here as well), the show aims to present an impressionistic portrait of the artist at a notably bittersweet moment in his career: the final, Christmas-themed broadcast of his NBC variety show in 1957 (though we don’t learn the date until well into the performance). On the one hand, Cole became the first Black host of a network TV show; on the other hand, he cut short the program after just over a year due to the failure to lure even a single nationwide sponsor. He’s an overwhelming success story who hit a ceiling dictated by the limits of American culture of the mid-20th century — but this show seems to want to chide him for not pushing harder, or more stridently against the forces aligned against him.

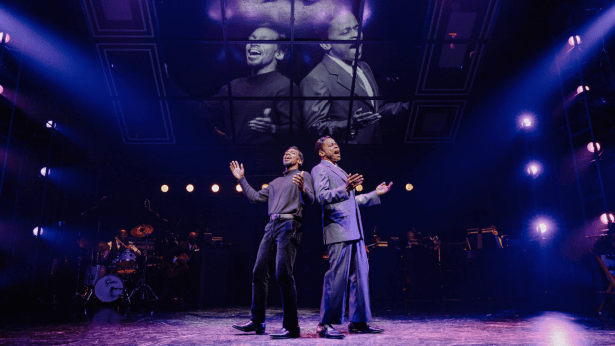

Dulé Hill brings a regal, sad-sack energy to Cole, and even manages to mimic the silky smooth vocalizing on numbers like “Nature Boy” and “L-O-V-E.” But after establishing the TV-studio setting, and Cole’s misgivings about donning makeup for his final show to appear fairer and less threatening to Southern audiences, the show quickly shifts gears with the arrival of Daniel J. Watts in a memorably energetic, spotlight-stealing performance as …. Sammy Davis Jr. Or, more accurately, a kind of Christmas Carol-style ghost of Sammy Davis Jr. who arrives to shake Cole out of his funk, or to awaken the social conscience of an artist whom many in the Black community had come to regard as too accommodating to the white majority. (Never mind that Davis — the Black Jewish Republican and celebrated pal of white Rat Pack stars like Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra — is an unlikely figure to be lecturing anybody, let alone Nat King Cole, against accommodation to white power brokers in the entertainment industry.)

“Some of you thought you were going to get a nice and easy holiday show,” Watts’s Davis tells us more than halfway through the show. “No! Welcome to the fever dream.”

By that point, though, it’s far too late for audiences to make any sense of the fever-dream book scenes — despite the shifts in lighting (by Stacey Derosier) on Clint Ramos’s handsome TV-studio set or the unsettling sound effects (by Alex Hawthorn and Drew Levy). These careen between flashbacks to moments in Cole’s past life — like his aphorism-spouting mother (Kenita Miller) trying to keep him out of trouble in Jim Crow-era Alabama — to present-day scenes of him battling a racist producer (Christopher Ryan Grant, in a truly thankless role) who implores him not to “monkey this up” for all those who worked hard to get him on the air.

Instead of dramatizing key events in Cole’s life, the show is mostly content to mention them in passing. We learn from an onstage reporter about the singer’s attack “by a Klan off-shoot group while performing in Alabama” — an incident that happened the very same year the show is set, and that also prompted a backlash from Black groups (including the NAACP’s Thurgood Marshall) who called on Cole to stop performing in segregated venues like the one where he was assaulted and to more publicly engage in the civil rights movement. But this show is silent on the particulars of all that, instead presenting a more simplistic view in which the ghost of Sammy sits on his shoulder like a woke Jiminy Cricket nudging Nat to stop appeasing fickle white audiences: “You up here worried that showing your pain will scare folks, but it’s your silence that is strangling you, so you better tell your truth while you’ve still got breath in your lungs to speak it.”

The one virtue of Lights Out‘s anarchic, anachronistic storytelling is that it allows the show to plunder the singer’s full catalog, including tunes like “L-O-V-E” written long after the 1957 setting. And the spirited production numbers are spectacular, showcasing not only Dulé’s vocal gifts and Edgar Godineaux’s choreography but also the talented cast: Ruby Lewis impresses as both a flirtatious Betty Hutton and the bubbly Peggy Lee, while Krystal Joy Brown shifts seamlessly from the sultry Eartha Kitt to dutiful daughter Natalie (who’s bizarrely introduced as both a 7-year-old and a teenager). In addition, Walter Russell III charmed as a young Nat (he alternates the role with Mekhi Richardson).

But the biggest scene-stealer is Watts, who so dominates whenever he takes the stage that you may wish that Sammy Davis Jr.’s name was in the title. Watts flashes a feral energy that’s truly magnetic, and he moves with a catlike grace around the stage — and occasionally the auditorium. His tap duet with Hill on “Me and My Shadow” (tap choreography by Jared Grimes) is a burst of percussive performance art. Lights Out is a showcase for some wonderful song and dance, but the luster dims whenever the band stops playing. ★★★☆☆

LIGHTS OUT: NAT KING COLE

New York Theatre Workshop, Off Broadway

Running time: 90 minutes (no intermission)

Tickets on sale through June 29 for $49 to $59