It’s easy to see why actors are drawn to the showy comedic roles in Yasmina Reza’s zippy three-man comedy Art, which is getting a zippy, high-profile revival on Broadway nearly three decades after its first Tony-winning run there. Reza has written juicy dialogue for her trio of longtime male friends who are mostly encamped in the upper middle class with all the comfort and privilege (and blind spots) that their status suggests.

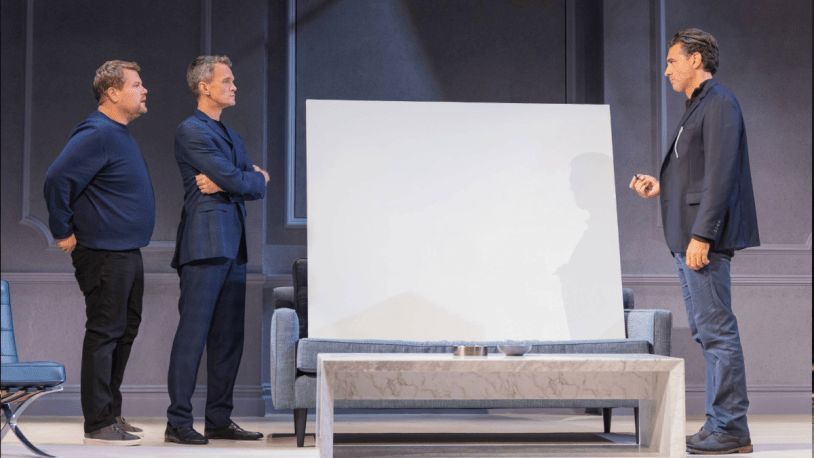

Bobby Cannavale, Neil Patrick Harris, and James Corden take to the roles with gusto, injecting each with vocal flourishes as well as sitcommish physicality (there’s a good deal of showy pointing and even jumping up and down to underscore the punchlines). The action kicks off when Harris’ divorced dermatologist, Serge, shows off the latest purchase for his geometrically sleek home (designed by David Rockwell): a stark all-white painting in the mode of mid-20th-century master Robert Ryman. His pal Marc (Cannavale), a happily married aeronautical engineer who carries himself with the easy confidence of an alpha bro accustomed to dominating all conversations, is taken aback — both by the canvas’s minimalism as well as the cost ($300,000, an inflationary bump from the $40,000 pricetag in the original 1998 Broadway production). Marc is no philistine, and we learn that he takes a certain pride in having introduced Serge to the poet Paul Valery back in the day.

But for Marc Serge’s gung-ho embrace of modernism is a bridge too Fauves. He not only insults Serge but lobbies their third-wheel buddy Yvan (Corden) to join his one-man opposition party — to what end is never exactly articulated. Yvan, a schlub who’s sputtered in both career and love, ping-pongs between his feuding friends in a vain hope of reconciliation. He just wants peace, especially since both men are expected to stand by him at his upcoming wedding to a woman who’s already hen-pecked him into the darkest, least comfortable corner of the matrimonial coop.

The premise of “Art” (which includes those telling quotation marks on the title page of the script) is rooted in a populist rejection of modern art fads, a kind of my-child-could-do-that mentality that already seemed dated in the 1980s. These still get knowing laughs of recognition/incomprehension from many in the audience. There’s nothing radically new about monochromatic canvases, of course, and lighting designer Jen Schriever cunningly allows us to see patterns and designs in the canvas as it’s moved about the set. Besides, objections to minimalist art seem passé compared to the more recent outrage over conceptualist work like Maurizio Cattelan’s banana-duct-taped-to-a-wall “The Comedian,” which sold for $6.24 million just last year. As Yvan points out when Marc complains that Serge has gone crazy, “If it makes him happy… he can afford it.”

Marc’s rejection is less about the painting than Serge’s enthusiasm for an intellectual pursuit he can’t fully understand or embrace. It’s a proxy for all the ways in which they’ve grown apart. Harris adds some telling physical flourishes as he stands behind his friends studying the canvas, eager to point to particular bits that he admires and then just as quickly restraining himself. His Serge nearly bursts with a puffed-up pride because he is able to afford an object so coveted by intellectual elites (though we get the sense that it’s definitely a splurge on the high end of his budget). Cannavale bounces off of Harris’s preening like a WWE wrestler on the attack, escalating his theoretical objections to a personal level with the speed of a sucker punch. And his reaction does seem to be personal, a sign of the distance that’s grown between them now that Serge has others to validate his newly cultivated tastes. As he tells Yvan, “I can’t love the Serge who’s capable of buying that painting.”

That leaves Corden caught in the middle, exasperated by the threat to their friendship as well as the stresses of his looming wedding and his newish job in his future uncle-in-law’s stationery business. The British actor is a wonderfully reluctant intermediary, a gifted sputterer who nails a breathless mid-show monologue of operatic domestic drama that rightly stops the show.

Art is entertaining middlebrow fare, a kind of Gallic update of the urbane comedy of manners that Neil Simon mastered in an earlier era. Reza is less interested in a serious debate about the nature of art than in how even the smallest issue can create fissures in long-term relationships, especially male friendships that aren’t centered on romance and family. Under the sprightly direction of Scott Ellis, the three stars display a crisp camaraderie that erases any doubt about an eventual reconciliation. No one is going to get unfriended.

In that sense, the stakes here are pretty low, as are the consequences of any fallout among guys who meet up only sporadically. This isn’t a family ruptured into embittered factions over MAGA hats or Bud Light or #BlackLivesMatter blackouts on social media, all objects signaling polar-opposite worldviews that are increasingly difficult to reconcile in the current cultural divide. And yet, wouldn’t it be nice to see how people who are no longer on speaking terms over some affront to their tribal identity might giggle and laugh at guys ready to fall out over a painting? And wouldn’t it be cheering to see how even a small gesture, like a mark with a felt-tip pen, might highlight a path toward detente? ★★★☆☆

ART

Music Box Theatre, Broadway

Running time: 90 minutes (no intermission)

Tickets on sale through Dec. 21 for $74 to $321