In the last decade or so, An Enemy of the People has morphed from an orphan in Henrik Ibsen’s celebrated oeuvre to one of the 19th-century Norwegian modernist’s most performed works. It’s an odd turn of events for a straightforward melodrama about a prickly doctor who rails against the insular, antiscientific prejudices of his hometown, taking on his own brother and the entire community to argue for his point of view.

But there’s something about this play — and its rousing defense of verifiable truth over powerful economic and communal forces eager to dilute or ignore its consequences — that has inspired modern theatermakers in the age of fake news and alternative facts. Doug Hughes directed a stirring production starring Boyd Gaines and Richard Thomas in 2012, and three years ago Robert Ickes oversaw a sleek version at the Park Avenue Armory built around two gimmicks: The audience assembled around tables where they voted on key questions that shaped the onstage plot, and the formidable Ann Dowd played all the roles.

Now, just weeks after German director Thomas Ostermeier premiered an updated Enemy of the People that features The Crown alum Matt Smith name-dropping Taylor Swift and playing in an Oasis cover band, Broadway is welcoming another forward-looking adaptation from playwright Amy Herzog, directed by Sam Gold in the immersive in-the-round Circle in the Square theater. Both new productions update the material for the Age of Trump and include elements of audience participation, casting theatergoers as townspeople called to bear witness to our hero and his stubborn quest to shut down the lucrative local spa due to his recently discovered proof that its waters are hopelessly contaminated and likely to cause disease and death.

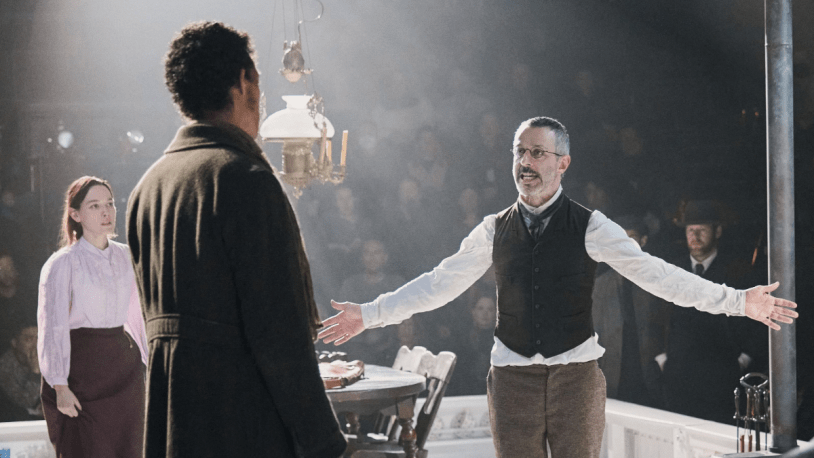

The fascinating but flawed Broadway revival also boasts star turns for two Emmy-winning actors, Jeremy Strong and Michael Imperioli, as the dueling Stockmann brothers. Strong gives a magnetic and driven performance as Dr. Thomas Stockmann, the physician who feels compelled not only to report his proof of contamination but to argue that addressing the problem, whatever the cost, is the only responsible path forward. Rejecting the kind of introspection and second-guessing that marked his performance as media scion Kendall Roy in Succession, Strong carries himself around the narrow strip of a stage (simply designed by the collective dots with wooden furniture, hanging oil lamps, and stenciled hanging eaves) with the determination of an unwavering crusader.

Imperioli seems more adrift as the doctor’s older brother, Peter, the local mayor (and Thomas’s boss) who’s bent on protecting his town’s economic interests. The former Sopranos star, whose thick mane of gray-white hair reflect the passage of nearly two decades since he played a Mafia foot soldier, declaims his lines without a hint of what his character might be thinking from scene to scene. Faced with a brother who threatens to upend his town’s livelihood, this Peter toggles between persuasion and threats — first to Thomas himself and then to malleable allies of the doctor’s like a pair of local journalists (Caleb Eberhardt and Matthew August Jeffers), who prove all to willing to abandon their high-minded ideals. But Imperioli’s line readings suggest neither menace nor exasperation, but an inscrutable sense of opposition as a default factory setting.

Herzog’s adaptation streamlines the story from its usual three-hour running time to a sleek two hours, killing off Thomas’s wife and instead making his chief domestic champion his schoolteacher daughter, Petra. Victoria Pedretti exudes level-headedness and filial loyalty as an educator who supports a vision of reason-based free-thinking and staunchly defends her father despite the increasing blowback. In addition, David Patrick Kelly makes a folksy impression as Thomas’s scheming tannery-owning father-in-law, while a scene-stealing Thomas Jay Ryan perfectly captures the weaselly town printer, who never vacillates from his commitment to moderation at least until he’s certain of which way the winds of public opinion are blowing.

Overall, there’s less subtlety and nuance in Herzog’s adaptation, which more explicitly draws out the modern-day echoes in an allegory about society’s willingness to defend the status quo and reject men of science (Dr. Anthony Fauci!). As a result, there’s no mystery as to which character should hold our sympathy — a tilt that is underscored by Gold’s staging, which elevates Strong onto a platform, brightly lit for the first time in the show (lighting by Isabella Byrd), for a speech to the community on behalf of science, the wisdom of the elites, and the imperative to sacrifice for the greater good.

That’s a choice that may be fitting for a character exhorting 2024 audiences to certain inconvenient truths: “A society that lives on lies deserves to be exterminated!” Thomas shouts. But it’s also a departure from Ibsen’s original, which treated the doctor as a much less sympathetic figure, one whose self-righteous elitism could harden into dismissive cruelty toward the idiot rabble he deemed too stupid or too stubborn to heed his Cassandra act. Strong’s Thomas tiptoes up to that line, at one point suggesting that the masses are in danger of behaving like sheep, even baaaing at them, but Ibsen’s bulldozed through it — making Thomas a victim of his own hubris as much as the mob’s enmity. (Ryan’s printer was not wrong when he cautioned Thomas, “You’re not going to get what you want by embarrassing people.”)

It’s a shame, because flawed heroes are more compelling than martyrs.